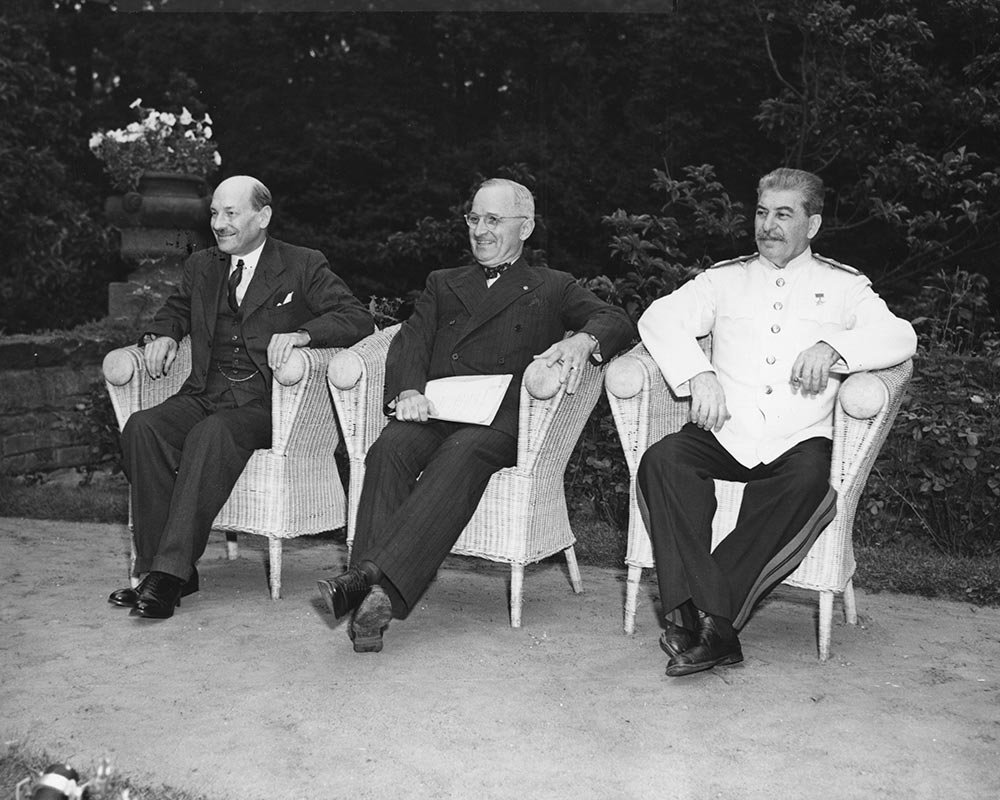

President Truman and Prime Minister Attlee received word early this morning that Stalin was still feeling ill and that his doctors had advised him to remain and rest at his villa for another day.

The eleventh plenary session was now suspended once again and it most likely could not have miffed the Anglo-American delegations more. Given all the off-record talks that had been going on over the last forty-eight hours, many were able to sense that agreements could soon be put into writing and everybody would finally be able to start heading home once Stalin had returned to the round table.

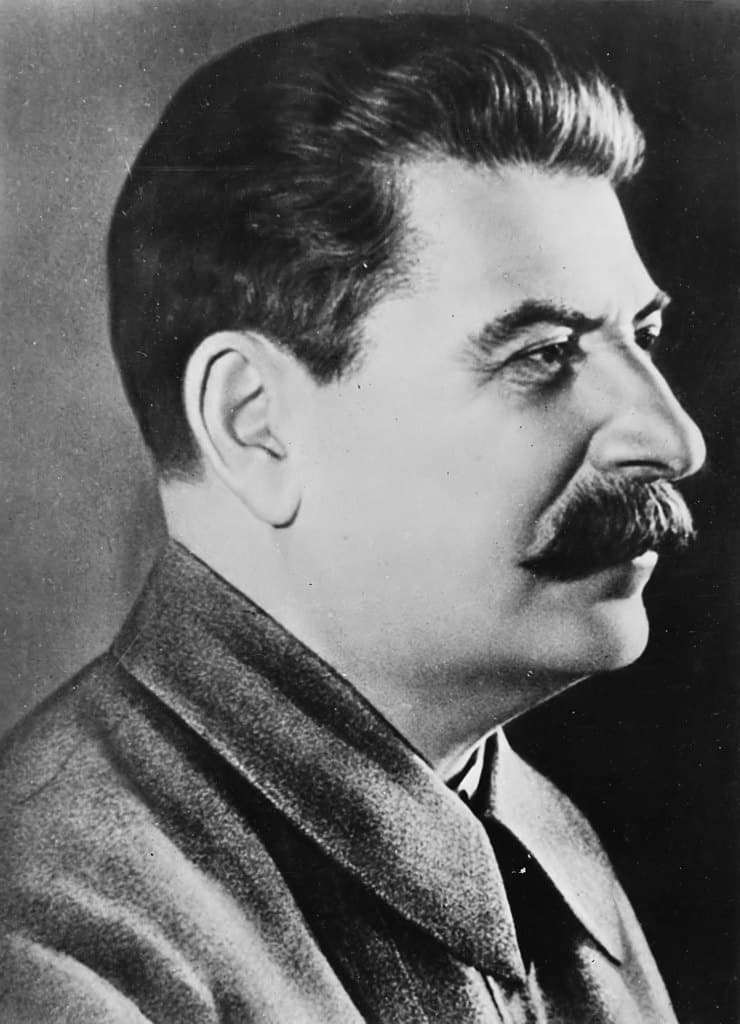

For someone to catch a cold toward the end of a warm July is not impossible, but it might seem a bit unusual if that person is healthy and fit; Stalin, however, was not healthy and fit at this time. In fact, his health had already begun to significantly decline toward the end of World War II.

Born in Gori, Georgia in 1878, Stalin had contracted a number of various illnesses during his early years as a child. Before the age of seven, he had suffered from measles, scarlet fever, a severe attack of smallpox – which left his face slightly disfigured – and probable poliomyelitis, which is an infectious viral disease that affects the central nervous system and can cause temporary or permanent paralysis. Early in life he had also suffered from severe pain and stiffness in his elbow, arm, and shoulder which could have been attributed to the poliomyelitis, or to one of three traffic accidents he had been involved in. Some have also claimed that this pain, which would trouble him his whole life, may have come from injuries sustained during his bank robberies as a young revolutionary, physical abuse inflicted by his father, or simply the result of a birth injury. At any rate, Stalin experienced more health problems at an early age than most people experience in a lifetime.

As an adult, things did not get much better for him healthwise. At age thirty-one he contracted typhus, which is an infectious disease caused by rickettsia (small bacteria transmitted by mites, ticks, or lice) and characterized by a purple rash, headaches, fever, and delirium, while he was serving a two year exile after getting into trouble with the police and engaging in Bolshevik activities. Twelve years later, after just being diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis, Stalin was operated on for appendicitis and experienced complications so severe that it caused his surgeon to fear for his life. Around the same time, he began having chronic dental problems that required a number of very painful procedures.

As Stalin approached fifty years old, he started to have frequent bouts with random abdominal pain that was accompanied by horrible flatulence and diarrhea, which was likely caused by irritable colon syndrome. All of this, coupled with his recurring joint and muscle pains that had tormented him since his youth, prompted his doctors to advise him to adopt a healthier lifestyle at the beginning of the 1930s. However, Stalin did not take their advice seriously and kept on overeating, drinking moderately to heavily, smoking cigarettes, and taking in essentially no exercise. Stalin refused all medical treatment, started to become hostile toward his doctors, and eventually began to experience frequent chest pains that would haunt him for the rest of his life.

Despite a wrap sheet of lifelong medical problems and a bout with a rather severe case of influenza in the fall of 1941, Stalin’s health surprisingly remained relatively stable during most of the war. But when he turned up late for the start of the Potsdam Conference, however, some who knew him best might have brought his health into question as being the reason for his tardiness. Stalin claimed that he got tied up because of official business, but this was also at the same time that his cardiac problems – which started to surface around ten years earlier – began catching up with him to the point where he had constant high blood pressure, frequent chest pain, and displayed an overall appearance that could be described as simply tired and unwell. Therefore, some historians have gone as far as to claim that Stalin’s delay was due to a suspected minor myocardial infarction, which very well could have been the case given his history of poor health.

Extreme paranoia had dramatically increased around this time as well. Stalin constantly feared for his safety and always felt that he had a target on his back after victoriously emerging from World War II as one of the most powerful human beings on earth. He was so cautious of his safety that his railway journey to Potsdam consisted of some of the most bizarre measures of security ever involved in protecting a world leader.

Stalin’s train consisted of several armored saloon cars, a car for guards, a staff car, a car-garage which contained two of Stalin’s armored vehicles, a dining car, and a wagon with food and beverages. For intense security measures, the train carried 80 officers and two makeshift platforms that were attached for anti-aircraft guns to be positioned on.

To ensure Stalin’s ultimate safety, up to seventeen thousand NKVD troops were employed to guard the route and every kilometer of road was protected by six to fifteen people. As the train traveled through the less desired parts of Poland and Germany, the local people were temporarily evacuated from the area around the railway and the shutters on the windows of houses facing the railroad had to be closed.

Even when he got to Cecilienhof, he quickly saw that the Soviet delegation had specifically chosen the wing that they occupied because it provided Stalin with an adequate office that had two doors that could be used as an escape exit. There was no way that anyone on God’s green earth was going to make it past the permanent security at the place, which was provided around the clock by the Soviets, as well as the swarms of American and British soldiers who were also on hand. Yet, Stalin’s paranoia would disagree and a lot of this needless anxiety that continually burdened his mind may have contributed to the episodes of dizziness that he had also experienced at this time.

So if Stalin was going to be absent from official business at Potsdam for another day because of a cold he had apparently caught, it was also most likely that he was dealing with other health issues that were the result of years of living with poor health.

–

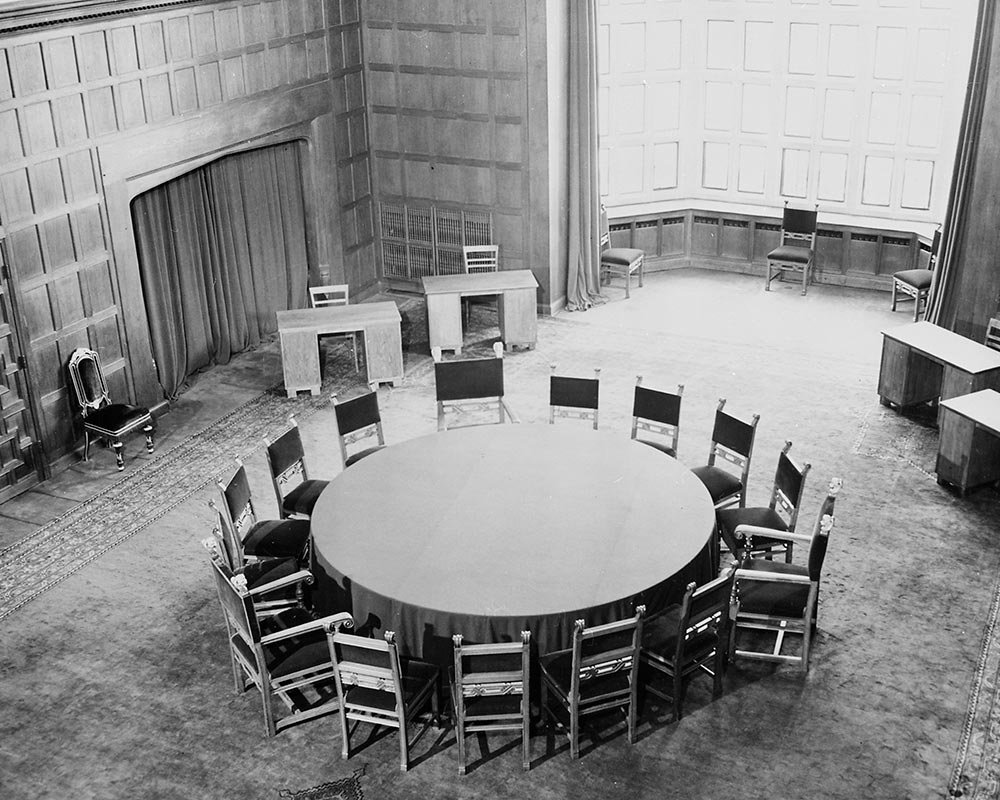

Since the eleventh plenary session was suspended for another day, the Foreign Ministers and their advisors decided to meet in place of the Big Three for the tenth time at 5:00pm in the conference room at Cecilienhof. The goal was to push closer to the finish line and hammer away at finalizing any agreements that they could since it was felt that some progress had been made during off-record talks over the previous few days.

The hope was that the views and positions of the Foreign Ministers did not differ too greatly from those of the Heads of State, so that all the three leaders would have to do is essentially sign off on any agreements presented to them at the next plenary session.

Minister Ernest Bevin chaired today’s meeting and presented the following topics to be discussed on today’s agenda.

- The invitation to the Governments of France and China to participate in the Council of Foreign Ministers.

- Notification to the French Government of the decision on political principles with respect to Germany.

- Reparations from Germany, Austria and Italy.

- Disposition of the German fleet and merchant navy.

- Political principles in the first stage of the control period in Germany—additional points.

- Yugoslavia.

- War crimes.

The Foreign Ministers and their advisors were quite familiar with most of these topics since several of them had already been extensively covered, and in some cases, heavily debated. The topic of ‘war crimes’, however, was a new one, but appeared to to be a topic that should not prove to be so contentious like the others.

When the agenda reached this topic, Molotov made a well deserved point that be believed that there would be many people expecting the delegations to address Nazi war crimes, especially since the world was learning more and more about the details of the horrors that Allied soldiers discovered while they liberated Europe from National Socialism. Molotov submitted the Soviet draft that proposed that the first ten war criminals who were currently in Allied custody should soon be dealt with:

“The Conference has found it necessary to organize in the very near future an International Tribunal for the trial of the important war criminals whose crimes are not connected with a definite geographical location and who, in accordance with the Moscow Declaration of November 1, 1943, are not to be sent to the countries in which their crimes were committed, to be tried according to the laws of these countries. The Conference has decided that the International Tribunal, first of all, must try the following leaders of the predatory Hitlerite band: Goering, Hess, Ribbentrop, Papen, Ley, Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Frick, Hans Frank, Streicher, Krupp and Schacht.The leaders of the three Allied Governments declare that, in accordance with the Moscow Declaration of November 1, 1943, they will take all measures at their disposal in order to ensure the surrender into the hands of justice of the war criminals who are hiding in neutral countries. In case of a refusal by any of those countries to surrender war criminals who hide on its territory, the three Allied Governments will consult among themselves concerning the measures which should be taken in order to ensure the carrying out of their inflexible decision.”

Secretary Byrnes also agreed and said that he had already discussed the matter of German war criminals with United States Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, who was leading the United States War Crimes Commission, but wanted to talk with him again to ascertain the status of the Commission’s negotiations.

There had been a disagreement as to the place where the tribunal should sit – whether in Berlin or in Nuremberg – and Molotov said the Soviets would agree to either place.

Foreign Minister Bevin felt that Nuremberg was the most suitable place to hold the proceedings. As this was the city in which the NSDAP held its annual party rally for so many years, it would be befitting to bring the criminals to justice in a city that was so highly revered among the party leadership and those who supported it.

The three Foreign Ministers agreed to return to the topic tomorrow after they had a chance to work out a few minor glitches. But in short, this proved to be one of those rare instances during the Conference that all three delegations could agree on an important topic in principle without a long and exhausting debate pursuing – a debate that would produce nothing more than a stalemate.

Back at the ‘Little White House’ in Babelsberg, President Truman hung around his villa catching up on his correspondence.

Earlier in the day, he had sent a letter to Stalin wishing him well and expressing regret to learn of his illness, and afterward he sent a consolation letter to Churchill, telling the former prime minister that he regretted his failure to return to Potsdam but wished him a long and happy life. He then wrote in his diary that he had given the USS Augusta Captain, James Vardaman, the order to set sail from Antwerp and ship to Portsmouth, England. The President was so desperately eager to get back home and if he flew from Berlin to Portsmouth immediately after the Conference, this would give them a two day head start instead of sailing across the English Channel.

“We are leaving from Plymouth, England which gives us 48 hours start of leaving from Antwerp,” Truman wrote in a letter to his wife the next day. “So if we get untied from the dock Friday afternoon by Thursday we’ll be in Norfolk, and then Washington the next day in the morning…I’ll sure be glad to see you and the White House and be where I can at least go to bed without being watched.”

**