Just five days after President Truman left Norfolk, Virginia on the USS Augusta to sail across the Atlantic Ocean, he wrote a letter to his wife moaning about how he was dreading his trip to Potsdam and claiming that it was “worse than anything” he had ever had to face.

For a captain in the United States 129th Field Artillery – who commanded and led just over 190 men into battle during World War I – to say that a “restful and satisfactory trip” (words he used in the same letter to describe his first few days at sea) to Germany to attend a summit, live in a huge villa, and negotiate peace talks in the former Crown Prince of Prussia’s palace were going to be the worst thing that he had ever had to face, demonstrated a lot about his attitude toward this trip before it had even begun.

Indeed, the President was certainly being sarcastic in his tone, but it revealed early on that his heart was not in the right place when it came to attending this conference from the beginning. Seventeen days had now passed since he sent that first letter – and the Potsdam Conference was now twelve days old – and nothing of significance had really been accomplished.

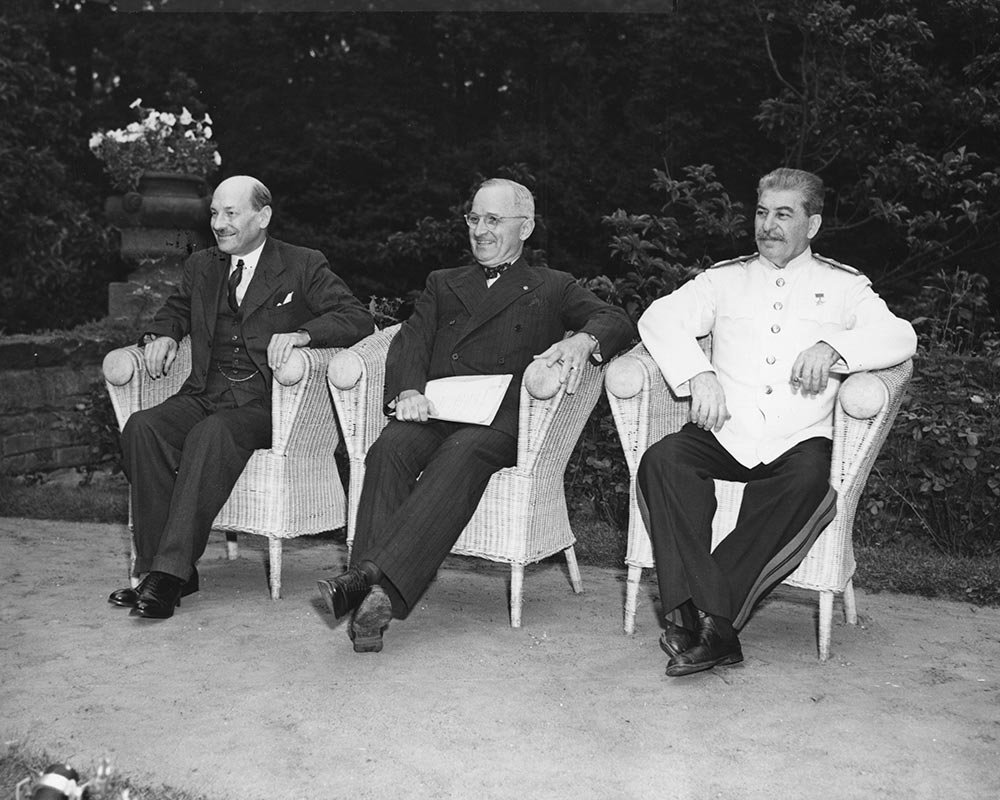

Therefore, today was supposed to be an important day at Potsdam. With the American delegation itching to head home and given the fact that the progress on the two most contentious issues of the conference – borders and reparations – were at a complete standstill, some leeway was hoped to be made when it had been agreed that Truman and Byrnes would meet with Stalin and Molotov off the record at the ‘Little White House’. Truman would write to his wife early this morning:

“Stalin and Molotov are coming to see me this morning and I am going to straighten it out.”

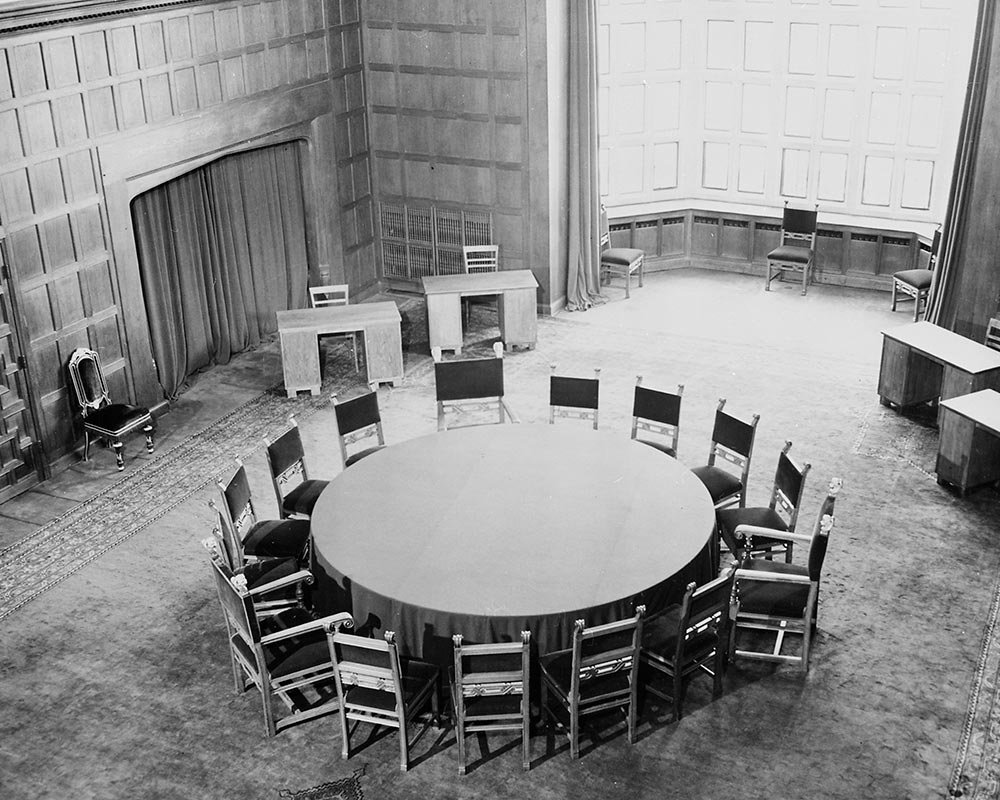

The intention was to meet in good faith, make reasonable suggestions on topics on which they disagreed, and try to build a path that they could follow together to on-record talks at the round table in Cecilienhof.

At 11:30am, Molotov arrived at Truman’s front door not with Stalin, but rather with his interpreter, Mr. Golunsky. As the American delegation watched the two Russians make their way into the villa, the questions on everybody’s mind was, ‘Where’s Stalin?’

“Marshal Stalin has caught a cold and his doctors will not let him leave his house,’ Molotov informed Truman and Byrnes. “He asked that President Truman excuse him for not coming to our meeting.”

After both Truman and Byrnes expressed their regret that Stalin could not attend today’s highly anticipated meeting, they both immediately knew that building a clear path to productivity being accomplished at Cecilienhof would have to wait. It would now just be Truman, Byrnes and Molotov engaging in redundant talks that would definitely have to be discussed again once Stalin was fit enough to join.

Given the unexpected change in plans, they could have all saved themselves a lot of time had they just decided to cancel today’s meeting and wait for Stalin to recover. Yet, they decided to still go on with the meeting and present what they had prepared, even if it meant going over it again when Stalin eventually returned. Truman then instructed Byrnes to take up the points he had had in mind to discuss today.

“In my opinion there are two principal questions that have remained outstanding,” Byrnes began. “If we could reach a decision on them it would be possible to consider winding up the Conference.”

To know surprise to anyone, the two questions at hand to which Byrnes was alluding were Poland’s western boundary and German reparations.

Upon Stalin’s suggestion at the start of the conference, members of the Polish Provisional Government of National Unity had been meeting with members of the British, Soviet and American delegations at various times over the last several days to present their views and to discuss the accession of territory that they felt they should receive in the north and west.

On July 24th President Bolesław Bierut had met with Byrnes, Eden and Molotov to argue for Poland’s claim to eastern Germany. At this time, Bierut chaired the State National Council (KRN) which was a political body – established at the end of World War II – whose parliament-like structure made it look democratic on the surface but was actually intended to be a communist-controlled center of authority that would challenge and rival members and factions of the Polish Underground State that remained loyal to the Government of the Republic of Poland in exile in London.

Bierut and his initiative was fully backed by Stalin and the Soviet Union when he gave his passionate declaration to the Foreign Ministers, pointing out that – the whole area for which they were asking to be given to them – Poland would still be smaller in total area than before the war because, in accordance with the Yalta Declaration, 69,500 square miles (180,000 square kilometers) of territory in the east would be transferred to Russia. He then asserted, however, that the eastern German area would give Poland a sounder economy and a more homogeneous population.

At the second plenary session, Churchill pointed out that this Soviet-supported plan would take nearly one-fourth of the arable land within Germany’s 1937 borders, forcing more than a million Germans into the western zones and “bringing their mouths with them”.

But by this point, however, for the sake of finally achieving something worthy of significance, the United States was willing to go further to meet the Soviets wishes in regard to Poland’s western frontier.

After much consideration and many hours of debate, Byrnes handed Molotov a document that illustrated how Poland’s western frontier should be defined according to the United States. The proposal conceded German territory by moving the border between Germany and Poland in 1937 – the starting point upon which Churchill, Stalin, and Truman agreed at the second plenary session on July 18th – west. It would start and cut through the Baltic city of Swinemünde in the north, then continue west from the city of Stettin to the Oder River. The border would run along the Oder and the eastern Neisse River up to the border with Czechoslovakia. The document ended by stating:

“The three Heads of Government reaffirm their opinion that the final delimitation of the western frontier of Poland should await the peace settlement.”

After the document was translated, Molotov immediately expressed his disapproval on the grounds that the American’s proposal excluded the Eastern and Western Neisse Rivers, territory that the Poles were most insistent upon receiving. Furthermore, Molotov even reminded Byrnes that this was an area of vital importance for Poland, something for which Stainislaw Mikolajczyk, the Prime Minister of the Polish government in exile during World War II, had made a most convincing and definite argument before the three Foreign Ministers just a few days before.

“This is true, but Poland might not receive this additional area at the (actual) peace conference,” Byrnes responded.

Byrnes went on to remind Molotov that the final determination of the boundary would be made at the peace settlement, so moving the border a bit farther west now – to satisfy Mikolajczyk, Bierut and Molotov – would be a premature move and jumping the gun, so to speak, especially since there was a strong possibility that the American proposal could be accepted when that meeting took place. Moreover, to solidify the Americans’ position and to highlight an agreement that the Soviets had forgotten up until this point, Byrnes turned back to Yalta and reminded Molotov that there would be four occupying powers in Germany; now, however, there was a situation where there was in fact a fifth – the Polish Administered Area – which had been assumed without consultation or agreement with the governments of the United States, the United Kingdom, and France.

“This was no one’s fault; it was an extraordinary condition, since all Germans had fled the region,” Molotov quickly replied.

“But we thought that this suggestion of ours would be agreeable to the Soviet Delegation since it is our opinion that it represents a very large concession on our part and we hoped that Mr. Molotov would submit it to Marshal Stalin,” Truman said.

“Of course,” Molotov replied. “But I can say here that Marshal Stalin is most insistent that this region as well should be placed under Polish administration.”

The Soviets were not budging on their demands and this should not have surprised Truman and Byrnes at the meeting given the fact it was the same behavior they had been seeing firsthand in Cecilienhof. If the Soviets hold their ground and force the Americans and British into a position where they would have to temporarily recognize the boundaries of their puppet controlled Polish Administered Area, then they would be well on their way of achieving their goal of building that band of protection to the west of the Soviet Union that they so desperately wanted.

After taking a big swing and missing on making some progress on the topic of borders, Byrnes quickly realized that it was time to move on to reparations.

Ever since Yalta, the great variance between the Soviet Union and the Anglo-Americans on the subject of reparations had been apparent. Indeed, it was mentioned that reparations should be obtained through payments ‘in kind’ rather in currency, but the Soviets still demanded the latter. Since Yalta and the subsequent meetings between the Commission on Reparations, the United States and Great Britain had been desperately trying to get the Soviet Union to abandon their demand that Germany should pay $20 billion to the Allies with half of that amount going to the Soviet Union.

During the Conference, Byrnes had countered this monetary demand with the idea that each occupying power would be allowed to take property as war booty from Germany from their own zones as reparations to either be exchanged between the zones or eventually have its value charged against whatever reparations program was later agreed upon. He then asked Molotov if he had had the opportunity to consider this plan.

“The proposal is acceptable in principle but our delegation would like to have clarity on certain points – in particular – the amount of equipment which would be turned over from the Ruhr to the Soviet Union,” Molotov replied.

Rich in natural resources, the Ruhr was one of the most industrial areas in all of Germany and it lay in the British Zone of Occupation. If this were to be the route taken toward reparations, then Molotov felt that heavy industrial equipment totalling $2 billion or five to six million tons from the Ruhr should be handed over to the Soviet Union.

Whether Molotov’s ‘five to six million tons’ meant the productive capacity or the actual weight of the equipment is unclear. At any rate, this was the first time since the Yalta Conference that the Soviets were showing signs of cooperation on the reparations front and an open willingness to compromise.

Although there was no agreement to an actual fixed sum and it was also pointed out that experts would have to do a long study on the exact value of the worth of the property, this was a huge step in the right direction and essentially the first time that some sort of progress had been felt during the whole Conference.

And at this point, progress could not have presented itself at a better time. Truman was getting homesick and he just wanted to leave. He wrote to his wife:

“It made me terribly homesick when I talked with you yesterday morning. It seemed as if you were just around the corner, if six thousand miles can be just around the corner. I spent the day after the call trying to think up reasons why I should bust up the conference and go home. Byrnes and I conferred all day…reparations and the Western boundary of Poland. If we can get a reasonably sound approach to those two things, we can wind this brawl up by Tuesday and we’ll head for home immediately.”

**