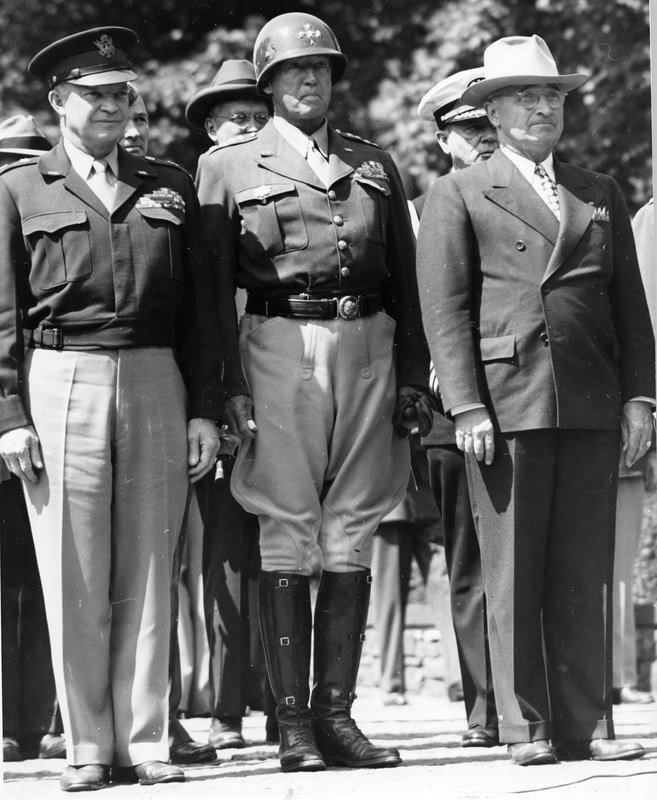

Late in the morning, Generals Dwight Eisenhower and Omar Bradley made their way to the ‘Little White House’ to meet with President Truman. They spoke about strategy in the Pacific and the use of the atomic bomb, on which the generals were brought up to speed about its successful test four days earlier.

Even though Truman did not specifically ask the generals for their opinions, Eisenhower said he opposed the use of the bomb, thinking that Japan was already defeated.

And Eisenhower’s thoughts on Japan’s defeat were correct.

At this point, the United States and its allies had been island hopping throughout the Pacific for years, seizing most of Japan’s strategic positions, and essentially pushing them back to their mainland. Furthermore, for a country with no natural resources, Japan was heavily dependent on imported wartime essentials like important raw materials – especially oil. Therefore, the United States systematically targeted and destroyed important shipping routes that resulted in a total collapse of their economy, the sinking of most of their fleets, and essentially a complete destruction of its navy. So not only did Eisenhower know that Japan was already defeated, but the Japanese knew it themselves.

However, knowing that Japan was defeated – on both sides – was not the issue at the end of the day.

The issue was getting Japan to surrender unconditionally.

This was the policy agreed upon at the Cairo Conference of 1943 when Roosevelt and Churchill met with China’s leader, Chiang Kai-shek, in Egypt to discuss and outline the allied position against Japan in the Pacific.

By signing the ‘Cairo Declaration’ on 27 November 1943, these three leaders – all at war with the Japanese – agreed that their governments would continue deploying military forces to the Pacific until Japan’s unconditional surrender.

The declaration stated:

“The Three Great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansion. It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed. The aforesaid three great powers, mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent. With these objects in view the three Allies, in harmony with those of the United Nations at war with Japan, will continue to persevere in the serious and prolonged operations necessary to procure the unconditional surrender of Japan.”

With defeat at Japan’s doorstep and the atomic bomb essentially finished, different opinions among the allied leadership began to surface on how to end the war. Not only did Eisenhower show initial disapproval of the atomic bomb, but he also expressed his hope to Secretary of War Stimson that the United States would not be the first to deploy the most terrible weapon in the world. Some years later, though, Eisenhower would concede that his reaction was personal and based on no analysis of the subject.

But if Truman – as implied in his diary – truly believed that ‘Manhattan’ would bring such victory instantly, this would have been the time for him to have said so. But he did not, which suggests that he was still less than sure about the bomb, or he still needed to make up his mind.

In any event, the days he had left to decide on using the bomb – or going ahead with the planned invasion of Japan – were numbered.

–

Following a quick lunch, the three hopped into an open air car and headed into to Berlin. Along the way, the air stunk of death and destruction, and they saw firsthand the miserable procession of German citizens in rags, pushing what few belongings they had through the rubble.

Truman recorded in his diary:

“You never saw as completely ruined a city.”

The scene was a tragic contrast from the dinner party the night before. While the heads of state pigged out on the most lavish food available, drank as many wines and spirits as they could, and enjoyed the entertainment of a concert pianist and violinist, thousands of displaced refugees were passing through the area on their way to a forlorn uncertainty. Among the human stench from dead bodies buried in rubble, were scenes of ruined buildings and burned out vehicles now littering the streets of Berlin’s once beautiful avenues.

The President and the two Generals arrived in the American sector at the US Group Control Council Headquarters for a flag raising ceremony.

The Stars and Stripes of the American flag raised that day was the same flag that was flying over the White House when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and on the following day when the United States declared war on Nazi Germany. From there, the flag had been on a historic journey. First the U.S. 5th Army raised it over Rome following its liberation of the city in June 1944, and the U.S. 4th Infantry Division raised it over Paris when it and other allied units entered and liberated the French capital in August 1944.

“We are here today to raise the flag of victory over the capital of our greatest adversary,”

Truman spoke without notes and with obvious emotion as he chose his words carefully.

“We are raising it in the name of the people of the United States, who are looking forward to a better world, a peaceful world, a world in which all the people will have an opportunity to enjoy the good things of life, and not just a few at the top.”

Unhooking his thumbs from the side pockets of his double-breasted suit, he freed his hands and chopped the air in unison as he then said:

“We want peace and prosperity for the world as a whole,” as he stressed each word with emotion.

“If we can put this tremendous machine of ours, which has made victory possible, to work for peace, we can look forward to the greatest age in the history of mankind. That is what we propose to do.”

It may not have been what FDR would have said or other presidents before him, but Truman’s short speech was decidedly moving. General Lucius Clay recorded:

“It was of lasting inspiration to all of us who were there…While the soldier is schooled against emotion, I have never forgotten that short ceremony as our flag rose to the staff.”

–

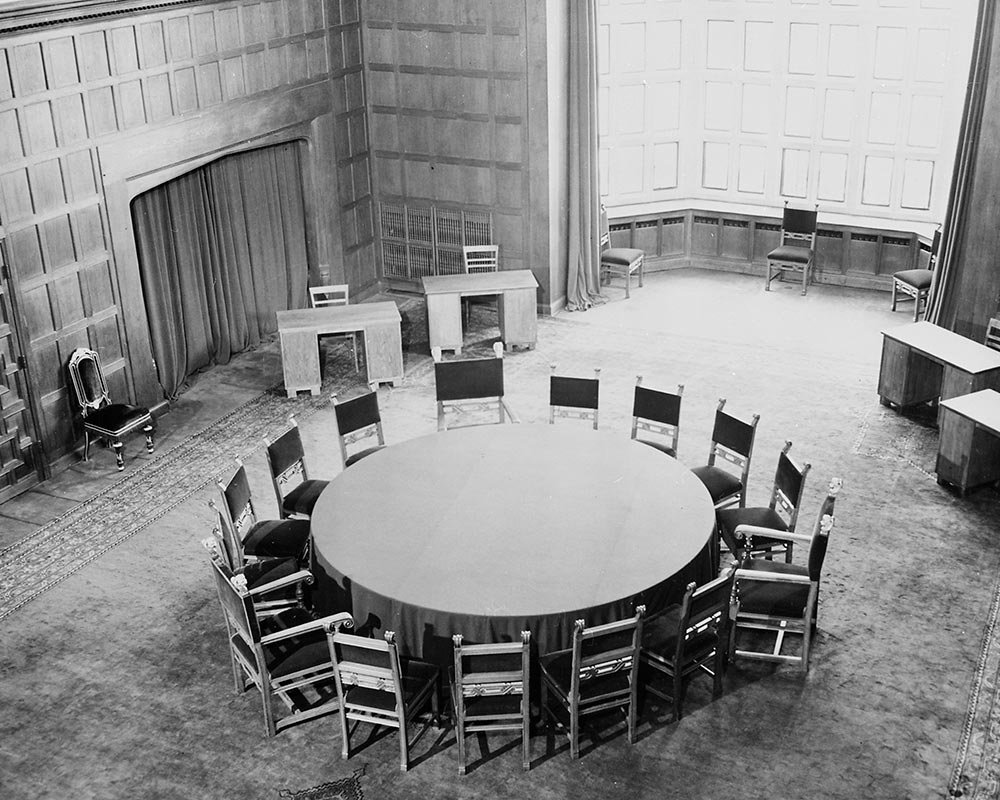

Following the ceremony in Berlin, the fourth plenary session of the Potsdam Conference was called to order at 4:10pm. The Council of Foreign Ministers and the subject of the treatment of Italy would dominate today’s brief session.

At the first plenary session, the Big Three approved the creation of a Council of Foreign Ministers, making it the first approved act of the Potsdam Conference. This council would be charged with the responsibility for sorting out the European settlements and preparing peace treaties. The only details left to discuss were the general logistics of where and when the council would meet.

Churchill immediately spoke up and said:

“I think the meeting place should be in London. London is the capital city most under the fire of the enemy and the longest in the war. It is the largest city in the world. It is more nearly half way between the United States and Russia than any place on the continent. I have twice gone to Washington, twice to Moscow, but London has not been used in the whole of this war. There is great feeling in England about this. I would ask my colleague, Mr. Attlee, to say a word on this.”

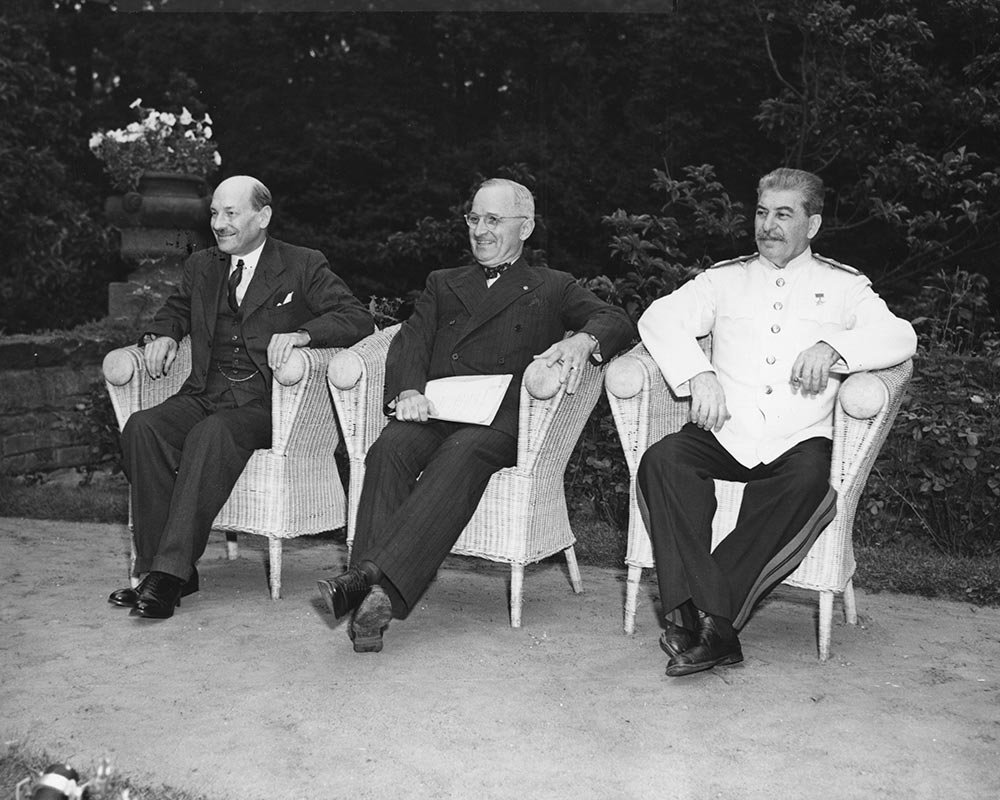

After Attlee shared his agreement with Churchill, both Truman and Stalin simultaneously agreed to the proposal on the table. It was an important logistical decision that was easily made among the leaders, and the Big Three would leave it up to the foreign ministers to decide when the first meeting would take place.

The next topic was discussing the future of Italy and this would dominate the rest of the session.

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had entered into an alliance with Nazi Germany in October of 1936 with the two powers claimed that the world would henceforth rotate on a so-called ‘Rome-Berlin axis’.

Following the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, Mussolini actually hesitated to join the war, understanding Italy’s material deficiencies and its army’s unpreparedness at the time. As Germany’s ‘Blitzkrieg’ was rapidly taking over Europe, however, Mussolini felt that the war would soon be over and realized that he wanted to sit in on dividing up the spoils. He said to his Army’s Chief-of-Staff, Marshal Pietro Badoglio:

“I only need a few thousand dead so that I can sit at the peace conference as a man who has fought.”

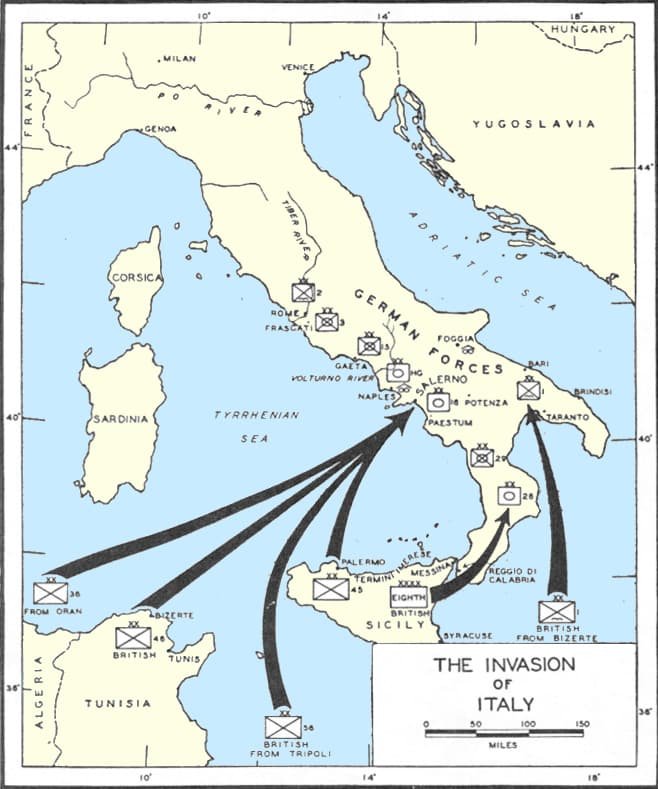

With the German invasion of France, Mussolini seized his chance and declared war on the United Kingdom and France on 10 June 1940. With some early success in parts of France and North Africa – and after involvement in Greece and Yugoslavia – the tide turned against Italy after the Anglo-American invasion of Sicily in July 1943.

After a quick campaign that resulted in allied forces reaching the toe of Italy and pursuing in swarms onto the mainland, Italian King Victor Emmanuel ordered Mussolini be deposed and arrested.

The Armistice of Cassibile was signed in Sicily a few months later in September, bringing an end to the war between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies. It was approved by King Victor Emmanuel himself and Marshal Peitro Badoglio, the new Prime Minister of Italy. The country remained a battlefield for the rest WWII as German troops rapidly moved in from the north to free Mussolini and fight alongside whatever Italian fascists were left in defeating the forces of the Kingdom of Italy, which had declared war on Nazi Germany on 13 October 1943. It was this declaration of war and fighting alongside Allied forces that the delegations at Potsdam looked to recognize.

Secretary of State Jimmy Byrnes was very adamant to achieve the goal of speeding Italy’s entry into the United Nations for not only helping to defeat Nazi Germany, but also to recognize its recent declaration of war on Japan. As a matter of fact, drafting Italy’s peace treaty became one of the first orders of business for the Council of Foreign Ministers after the Big Three approved its formation at the first plenary session.

It was now four days later. And the foreign ministers were ready to put the topic of Italy on today’s agenda.

Unfortunately, it became quickly apparent that this topic was more complex than anyone could have imagined.

After Truman echoed Secretary Byrnes’s adamance at the roundtable that a peace treaty should be quickly drawn up and admission into the United Nations be granted, Stalin fired back by essentially saying that it would not be that easy. He felt that the foreign ministers should further discuss the matter and not exclusively deal with Italy, but rather deal with it at the same time when they deal with the other satellites like Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary:

“We have no right to single out Italy. Italy helped Germany. Bulgaria and Rumania moved their troops against Germany. I am bound to say that their armies fought well. Finland did not give support in the war against Germany, but her position is all right and should be facilitated. The same applies to Hungary. It would be well in facilitating the position of Italy to facilitate the positions of the other satellite countries.”

Truman reiterated his position on recognizing the satellites of which Stalin spoke, but wanted to be certain that free and fair elections would take place in these countries, so that they can become self-supporting in the future.

Churchill fell somewhere in the middle. On the one hand he sympathized with Italy and made it clear that he supported peace and was anxious to send a message to the Italian people informing them of this, but he also pointed out that Italy’s hostile actions against the United Kingdom caused a great deal of suffering – on so many levels during the war – that he could not just simply acquit the country of its culpable behavior. He stated:

“I think we agree that preparations of the peace should be referred to the Council of Foreign Ministers. I merely point out we can not give up the surrender terms while we prepare peace terms. There is no objection to announcing peace treaties with Italy will be prepared—and also with the satellite countries.”

So it was agreed that the issue of peace with Italy would go back to the foreign ministers for more steps to be considered before a decision could be reached on peace with Italy.

The Soviets and the British had firmly applied the brakes to the Americans’ desire to quickly mend fences with Italy and steadfastly approve its membership to the United Nations, but for different reasons.

The British wanted to hold Italy accountable for its actions earlier on in the war and felt that the foreign ministers should carefully examine the road to a lasting peace. Stalin, on the other hand, could clearly sense the Americans’ enthusiasm and persistent urgency on the matter that he thought he could ‘throw Italy into the package’ and get them to also recognize the governments of Romania, Hungary, and Bulgaria at – or around – the same time.

These were countries where Soviet forces had been stationed for months recruiting individuals – and putting the wheels in motion – that would ultimately form Soviet-style governments sympathetic to Moscow.

It was a clever, yet duplicitous manoeuvre on Stalin’s part and a tactic that would become more familiar to the Americans and British in the future.

At the ‘Little White House’ later that night, Truman recorded in his diary:

“Uncle Joe looked tired and drawn today and the P.M. seemed lost.”

With most of the topics on the agenda heading back to the foreign ministers, once again, very little was accomplished.

**