Before heading to bed last night, President Truman opened up his diary and wrote about his impressions and reactions from his earlier afternoon tour in Berlin. He ended his entry with:

“What a pity the human animal is not able to put his moral thinking into practice…I hope for some sort of peace – but I fear that machines are ahead of morals by some centuries and when morals catch up perhaps there’ll be no reason for any of it.”

At 5:29am in New Mexico (1:29pm in Berlin) the previous day – while Truman was on his tour and thinking about how the nefarious human animal was not able to put his moral thinking into practice – the United States successfully tested the world’s first atomic bomb. The nearly five year old nuclear program – code named the ‘Manhattan Project’ – was now almost finished.

The Manhattan Project was conceived out of the fear and understanding that Germany was engaged in a nuclear program of their own in the 1930s.

In 1938, German chemists Fritz Strassmann and Otto Hahn barraged uranium with neutrons which resulted in the detection of the element, barium, something that was interpreted as a nuclear fission soon thereafter by Austrian scientists Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch. Once this information traveled out of Germany, many began to fear that Hitler would not hesitate to use a nuclear weapon if this new science were to assist in developing one.

After top scientists like Albert Einstein urged the United States government to respond to this harrowing new potential threat, President Roosevelt appointed various scientists and military officials to form a committee and conduct research to find out how uranium could be used as a weapon.

This so-called ‘Advisory Committee on Uranium’ would soon become the ‘Office of Scientific Research and Development’ (OSRD) in 1941 which is also around the same time that Italian scientist Enrico Fermi – who fled Italy in 1938 to escape the Italian racial laws that affected his Jewish wife – brought his expertise in nuclear chain reactions to the committee. Eventually the United States Army Corps of Engineers joined the ORSD after the U.S. officially entered WWII, making it a highly classified military operation with some of the world’s most brilliant scientists – many of whom had fled fascism in Europe – assisting the program.

After the ORSD formed the Manhattan Engineer District and based it in New York City (Manhattan) under the leadership of then U.S. Army Colonel Leslie Groves, it was on December 28, 1942 that President Roosevelt authorized the formation of the Manhattan Project. Its aim was now to put forward the research and science to craft a weapon out of the elemental forces of the universe at three different facilities across America, with the main facility being in New Mexico under the leadership of renowned physicist Robert Oppenheimer as the Los Alamos director. It became the responsibility of Groves to relay the scientists’ progress in the project to the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, who was then responsible for officially informing the President of the United States.

So when President Truman returned to Babelsberg late in the afternoon yesterday, there stood Secretary Stimson waiting to give President Truman a decoded message that read:

‘Operated on this morning. Diagnosis not yet complete, but results seem satisfactory and already exceed expectations.’

Truman would still have to wait a few days before he received a detailed report of the blast, but he now knew that the bomb would work and he would soon have to decide on whether or not to use it against Japan.

–

“Promptly a few minutes before 12:00, I looked up from my desk and there stood Stalin in the doorway,” the President wrote in his diary. “I got to my feet and advanced to meet him; he put out his hand and smiled. I did the same, we shook, I greeted Molotov and the interpreter and we sat down.”

Joseph Stalin was the second Russian whom Harry Truman had ever met. The first and last Russian with whom he had sat down was currently standing next to Stalin and it is probably safe to say that an elephant had also followed the Soviets into the ‘Little White House.’

On April 23rd 1945 Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov made a brief stop in Washington to visit Truman on his way to attend the newly formed United Nations in San Francisco. Having read through the minutes and briefings from the Yalta Conference that had taken place just months before, Truman thought that the Soviets were breaking some of the agreements they had made at the meeting, particularly as it pertained to their current occupation of Eastern Europe and showing that they were doing nothing to organize and set up ‘free and democratic’ elections to take place in Poland. And Truman did not hesitate to give Molotov a piece of his mind.

The President of the United States shockingly gave the Soviet Foreign Minister a tongue lashing “in words of one syllable” as Truman would later recall. He essentially questioned why the Soviets were not behaving themselves or respecting the agreements that the Grand Alliance had made at Yalta.

After Truman’s tongue lashing had ended, an incredulous Molotov apparently drew back in a very formal and frigid way and claimed that he had never been spoken to in the way that he just had. According to interpreter Chip Bohlen, who was also at the meeting, Truman responded to Molotov by essentially saying that if the Soviets do not wish to be talked to in such a way then they should behave themselves.

Truman’s first rodeo in foreign policy ended with his boasting shortly thereafter that he had just given Molotov “the straight one-two to the jaw” – a way of saying that he wanted to convey the message to Stalin that the Soviet leader should stick to his agreements. It also demonstrated that Truman was the new sheriff in town. His approach to foreign policy was to take a tough stance against the spread of communism and speak in the language of strength, something he would later claim was the only language that the Soviets understood.

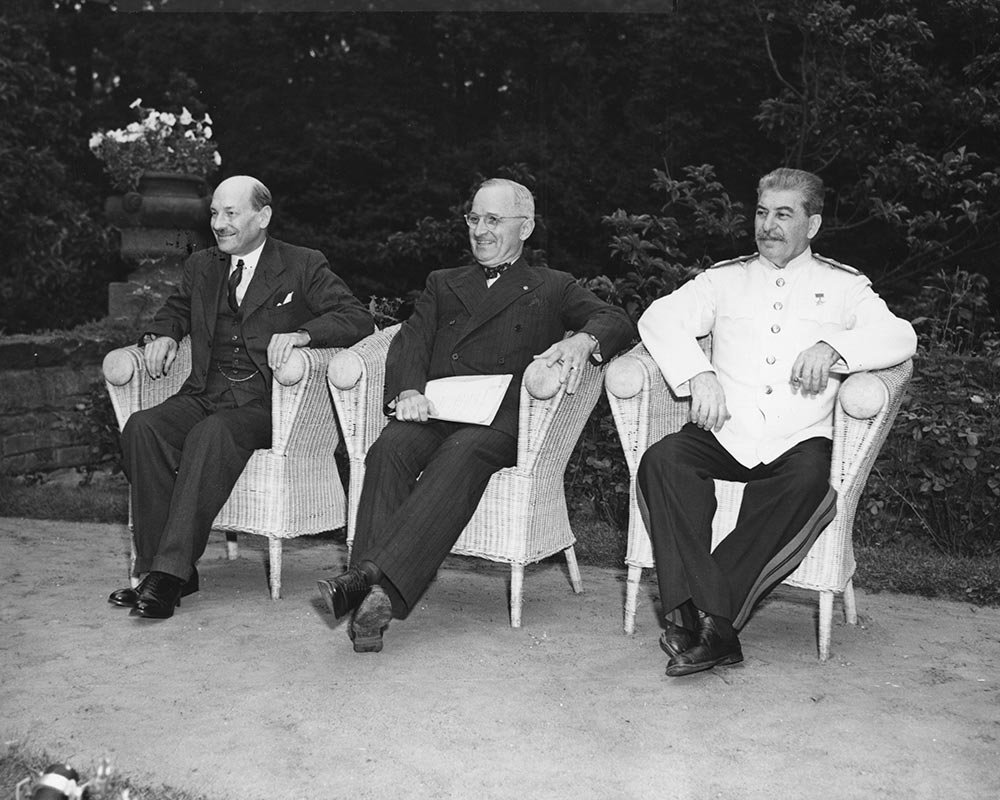

But when Stalin and Truman met each other for the first time, the atmosphere was warm and friendly.

The two leaders sat down, exchanged some kind words with one another and then began to engage in off the record, pre-conference talks.

Truman began in a firm, yet respectful tone:

“I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument,” he wrote that evening in his diary. “It pleased him.”

After briefly talking about the Soviet agenda which included the removal of Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco and dividing up Italy’s colonies – two topics that would dominate later on during the plenary sessions – Truman got what he had mostly come to Potsdam for: Stalin gave his word that the Soviet Union would enter into the war with Japan by August 15th.

Soviet commitment in the Pacific was a plea of which Stalin denied Roosevelt at Yalta while his forces were still fighting the German Army. Now, with war in Europe over, evoking Soviet help against Japan could once again be attempted.

Truman was not keen on coming to Potsdam and he wrote in his diary how much he dreaded it before it had even begun. Yet, despite his lack of experience, he knew that diplomacy was a face-to-face business and securing Soviet help – primarily taking on the Kwantung Army in Manchuria – would be vital to the United States’s early November invasion of mainland Japan, which he had authorized on June 18th.

“I can deal with Stalin,” Truman wrote later on in his diary. “He is honest, but smart as hell.”

It had been a productive and cordial first meeting that was complemented with drinking toasts, laughter, and cheerful pictures in the backyard – a far cry from Truman’s and Molotov’s highly tense meeting in late April. But despite the joy and high spirits, Stalin knew deep down that he and his armies were in a firm and unyielding position to surrender very little beyond the ultimate interests of the Soviet Union when the negotiating began at Cecilienhof.

–

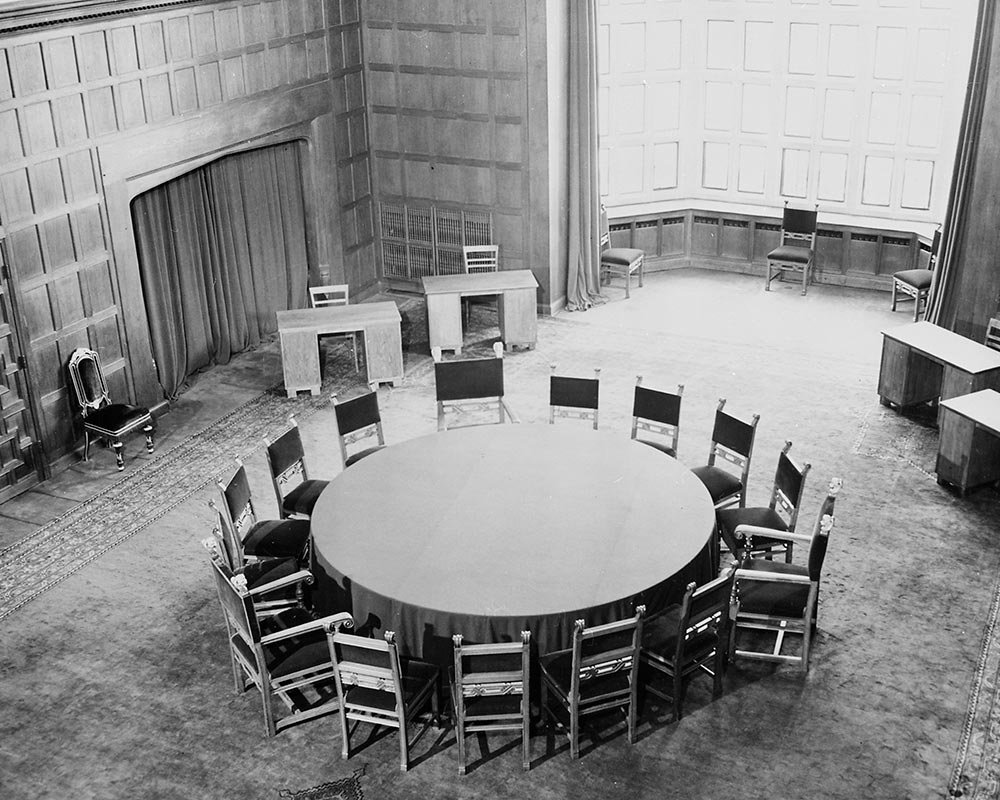

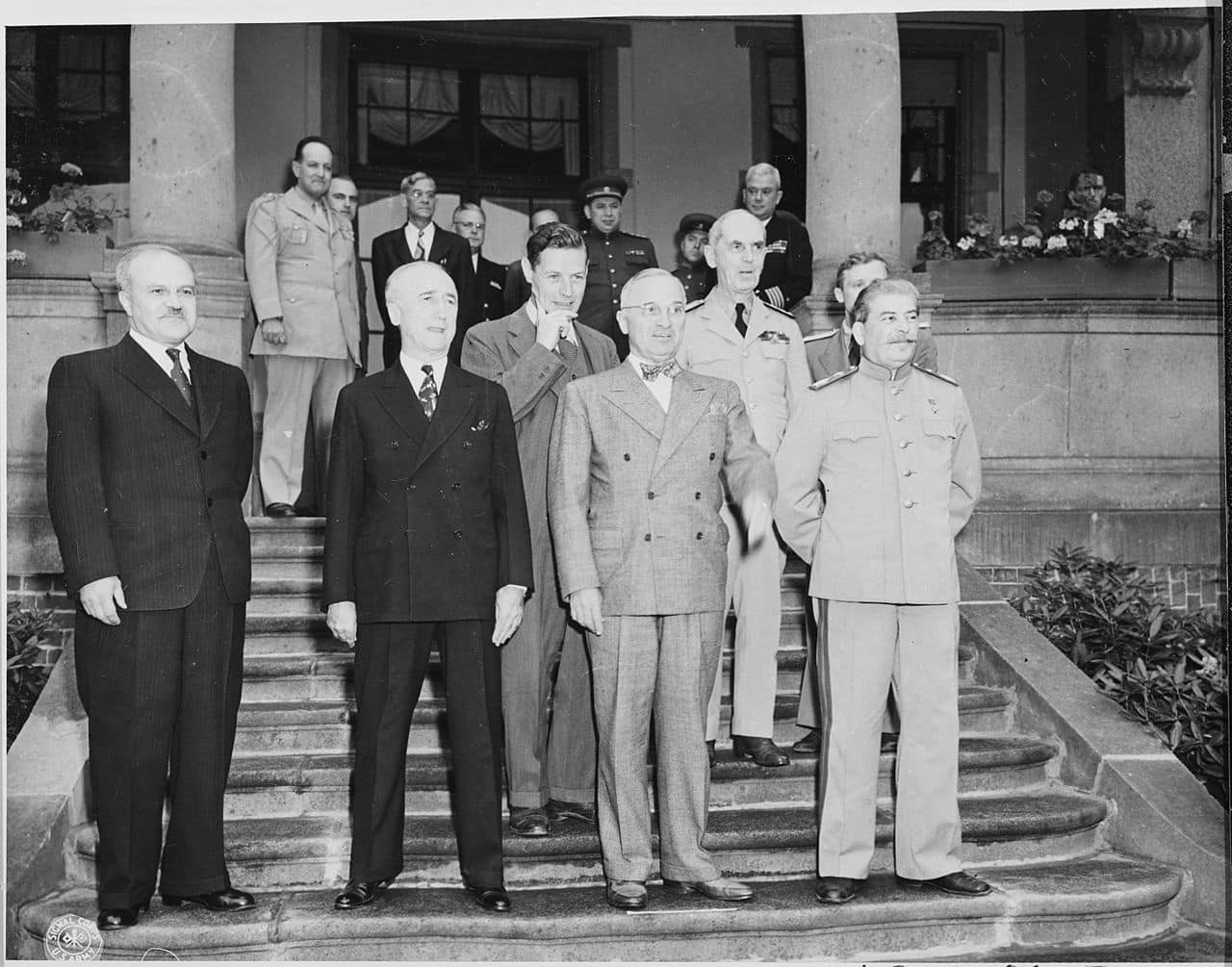

Just after 5:00pm on July 17th 1945, Churchill, Stalin and Truman made their way into Cecilienhof’s Great Room to sit down at the round table to decide Germany’s and Europe’s future. Prior to this summit, the focus of the previous two meetings had primarily been on a united fight against fascism.

With Hitler, the Nazis, and the various Axis dictators and sympathizers throughout eastern and central Europe gone, the Grand Alliance would now have to present their agendas and negotiate their differences as they embarked upon their ultimate quest of securing a lasting peace.

Joseph Stalin sat down at the table with the American delegation to his left and the British delegation to his right. Slightly slouched in his armrest chair, he looked calm and composed as he lit a cigarette and stared across the table at Truman and Churchill with English being spoken all around him. As he sat there puffing away and wondering how the negotiations would pan out, he was sure of one thing: mother Russia had paid the heaviest price when it came to their joint effort to defeat European fascism.

Although statistics are an imprecise and impersonal measure – and there remains some doubt about Soviet figures – the discrepancy between the wartime casualty numbers of the Soviet Union and of the Western Allies bears deep consideration. Current estimates place the number of British battle deaths at 383,800, and American battle deaths at 416,800. These numbers, although enormous by the historical standards of their place and time, absolutely pale in comparison to the Russian figures, which current estimates place at somewhere between 8.8 million and 10.7 million. Even the range of uncertainty between these figures (about 1.9 million human beings killed) is more than two and half times the number of battle deaths suffered by the British and Americans combined (800,600). In other words, the Soviets had more men killed in battle in the three weeks of intensive fighting from January 12 to February 4, 1945, than the Americans had on two fronts the entire war.

The difference in the number of civilian deaths underscores the Soviet sacrifice even more starkly. The British lost 67,100 civilians in the course of the war, while the Americans lost 1,700 civilians. Compare these figures to an estimated 14.6 million Soviet civilians and the full magnitude of the Soviets’ suffering becomes unfathomable. Russia had lost 13.9 percent of its prewar population. By contrast, the British lost 0.94% and the Americans 0.32%. Such enormous numbers often fail to make the point or become confusing by their sheer enormity.

As Stalin himself once said, “one death is a tragedy’- a million deaths is a statistic.”

And sometimes smaller numbers tell the story better. To cite one poignant example, the city of Stalingrad, which had a prewar population of 850,000, had just nine children with both parents still alive at the end of the war.

Other numbers also stagger the imagination. In four years, the Soviet Union lost 1,710 towns, 70,000 villages, 32,000 factories, 65,000 kilometers of rail lines, 100,000 farms and an estimated 30 percent of its national wealth. The war also left the nation with approximately 25 million people homeless. The standard of living of the average citizen, a 1947 Soviet report noted, was “the lowest imaginable.”

In short, the Soviets’ interpretation of these figures and the sheer weight that they carried in the summer of 1945 played a pivotal role when it came to Stalin’s mindset at the roundtable. He felt that Russia’s wartime deaths, casualties, and sacrifices did not even come close in comparison to the amount of suffering that the British and Americans faced both at home and on the battlefield. Stalin not only believed that the Soviet Union was entitled to the largest piece of the pie or the highest degree of spoils, but these figures also convinced him that his interests vastly outweighed any position that Truman or Churchill were to take during the conference.

At 5:10pm the first of what would be thirteen plenary sessions was called to order. At Stalin’s suggestion, the Soviet and British immediately and collectively confirmed President Truman as Chairman of the Conference. Truman gladly and modestly accepted and began to present some of the proposals that he and his Secretary of State, Jimmy Byrnes, had prepared on their journey across the Atlantic for consideration. Byrnes would later write:

“It was evident that the other heads of government appreciated the President’s efforts in having proposals (on the first day) ready for discussion.”

–

The Big Three used the first session to get the lay of the land and to observe each other’s interactions and initial positions on issues that they felt should be put on the official agenda to be discussed and decided on during the summit.

President Truman introduced the Potsdam Conference’s first order of business by pointing out the urgency of establishing a ‘Council of Foreign Ministers’ that would be responsible for sorting out the European settlements in Germany and in the other nations that were part of the so-called ‘Rome-Berlin Axis’ during WWII. This council would be headed by the foreign ministers from France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States, who would then be responsible for reaching postwar political agreements and producing treaties that would all then be presented to the heads of state of these nations for a final approval.

An interesting moment in the session came moments later when The Big Three exchanged personal sentiments when the late President Roosevelt’s name came up. Truman had proposed that Italy – who had recently entered the war against Japan – be admitted to the newly founded United Nations and that an establishment of peace be made. Churchill responded with the belief that the heads of state were preparing to deal with very important policies somewhat too hastily and discussed how Italy had entered into the war against the United Kingdom at a very critical time. He then said that even President Roosevelt understood how Britain had been stabbed in the back by Italy with reference to Italy’s entrance into the war.

“I had to step into the place of a man who really was irreplaceable,” Truman responded as he also pointed out that he deeply understood that Roosevelt had gained the Prime Minister’s and Soviet dictator’s good will and friendship both for himself and for his country.

Truman went on to say that he hoped that he himself might be able to succeed in part of that friendship and good will.

“I feel certain that both the Marshal and I would like to renew the great regard and affection that we had for Mr. Roosevelt with Mr. Truman,” Churchill responded. “Our common friendship had served to hold our countries together in the most trying period of history. Mr. Truman has come to join us at a most critical time. I extend my cordial regard and respect to Mr. Truman. I have every hope and confidence that the ties that bound our nations together will continue.”

“On behalf of the whole Russian delegation,” Stalin replied, “I express the desire to join in the sentiments expressed by Mr. Churchill.”

There was a deep amount of admiration and respect that could be felt among the heads of state. Truman was determined to carry on the legacy of Roosevelt as he negotiated at Potsdam while Stalin and Churchill looked for qualities in Truman that they could deal with as they got to know the new president.

The Big Three took their turns presenting the issues that they wanted to be added to the official agenda. Stalin, who was fiercely protective of his interests, was very keen on discussing the division of the German merchant fleet and navy, war reparations, trusteeships for Russia, and dealing with the Axis satellite states. To no surprise, Churchill, on the other hand, was very keen on discussing the Polish question.

“We hope the Marshal and the President will recognize that England was made the home of the Polish government which fought against the Axis,” Churchill announced. “With regard to Poland, Britain attaches great importance to the election that should give the people an opportunity to realize their wishes.”

The foreign secretaries, Byrnes, Eden, and Molotov were going to be the hardest working statesmen at the conference.

It was their responsibility to record and analyze the positions of the heads of state, discuss them and then prepare an agenda with issues on which The Big Three would decide. Throughout the entire conference, they would meet most mornings, sit in on meetings within the subcommittees, and on occasion even meet in the evening following a plenary session. They had to play their cards carefully as they not only expressed their own judgments, but they also represented the interests and the positions of their country’s leaders. Stalin even made a joke at the roundtable when he said:

“As all the questions are to be discussed by the foreign ministers, we shall have nothing to do.”

A tired and ill-prepared Churchill felt that the foreign ministers should provide three or four points for discussion each day, which he felt should keep them busy. This put Truman on edge who explained that did not come all the way to Germany to just simply discuss.

“I want to decide,” he forcefully responded. “So you want something in the bag each day?”

Churchill replied as he was now beginning to see the difference between Truman and Roosevelt. Truman told the Prime Minister that he was correct and that tomorrow he wanted to start earlier. “I will obey your orders,” Churchill responded, and a moment later, Stalin’s eyes brightened, knowing that he had an opportunity to throw in a jab.

“If you are in such an obedient mood today, Mr. Prime Minister, I should like to know whether you will share with us the German fleet?”

Churchill questioned why Stalin was inquiring about the fleet and exclaimed that it should either be destroyed or shared since weapons of war, he felt, were horrible things.

“Let’s divide it,” Stalin said. “If Mr. Churchill wishes, he can sink his share.”

Anthony Eden thought that Churchill’s performance at the first meeting had been pathetic.

He described the Prime Minister as “wooly and verbose,” and too much under Stalin’s spell. British Permanent Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs Alexander Cadogan told his wife in a letter that Churchill simply talked too much, while Truman was admirably businesslike.

After Truman adjourned the first plenary session, the three leaders moved next door to the Weißer Salon. This large, bright and cheerful room was the Crown Prince’s and Crown Prince’s wife’s music room. During the conference, though, it served as the Soviet’s reception hall where Stalin’s delegation had prepared a lavish and elaborate buffet for the Americans and the British.

From what President Truman would recall, it became clear that the Soviets really knew how to put on a buffet at day’s end: “The table was set with everything you could think of…Goose liver, caviar, every kind of meat one could imagine, along with cheeses of different shapes and colors, and endless wine and vodka.”

The reception lasted under an hour and the three leaders made their way back to Babelsberg.

Tomorrow was going to be a busy day.

**