July 16th 1945 was intended to be the first day of the Potsdam Conference – but with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin delayed for a day, the Anglo-American delegations took the opportunity to situate themselves.

US President Harry Truman would arrive to take up residence in Babelsberg, near Potsdam in one of three historic houses that made up this quaint lake shore community. His British counterpart, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, was staying nearby and a meeting between the two would be the first major item on the daily agendas of both leaders.

Eager to get the lay of the land, each would venture separately to the ruined capital of the ‘Thousand Year Reich’. To assess the damage wrought upon the city in the defeat of Nazi Germany and prepare.

The Potsdam Conference was to provide the foundations of a lasting peace in Europe. But nothing could formally begin until Soviet leader Stalin arrived.

–

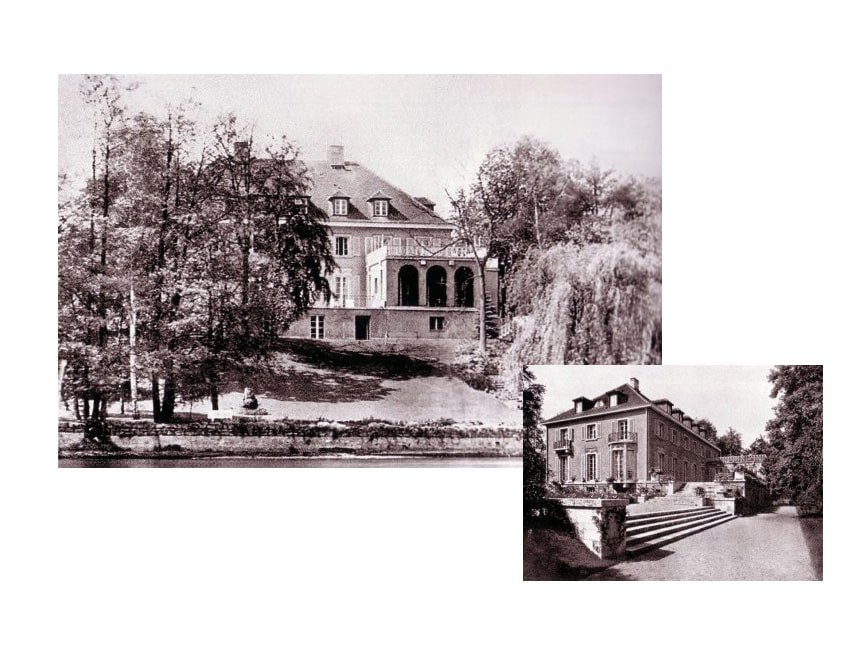

Before WWII, 20 year old Marie Louise Gericke and her family had been living an upper-class life in an austere, yet striking early 20th century neoclassical villa on the shore of lake Griebnitzsee in Babelsberg, Potsdam.

Located at Ringstraße 23, it was called ‘Villa Urbig’, named after its builder, banker Franz Ubrig whose daughter married Marie Louise’s father years after her mother had passed away. She enjoyed a pleasant teenage life there, taking strolls through the charming neighborhood and refreshing swims behind her backyard on hot summer days.

But in the spring of 1945, her living situation could not have been more different from the cheerful and welcoming days of her youth. After her father and step-mother had moved to Bavaria with her younger siblings to escape the Allied air raids on the area, she was now living in the large empty villa with just her aunt when the Soviets entered her street and came banging on the door. “The usual,” replied Marie Lousie when asked in an interview years later about what happened when the Soviets had arrived. “But enough has been written about that.”

The chaos and looting lasted for six weeks until one Saturday night at 11:30PM the Soviets returned to the front door holding flashlights. This time they were officers, dressed handsomely and looking as though they were men of significant importance. As the small flashes of light were dancing all over the walls, they told Marie Louise and her aunt that they were looking for villas with large rooms and asked them whether they knew of any suitable ones nearby. Well familiar with the sheer size of their own villa, Maria Louise and her aunt immediately sensed that it would only be a matter of time before their home was chosen.

A matter of time came Monday morning when the politely spoken officers returned.

“I’m sorry, but I’m afraid that you will have to leave this beautiful home,” one of them said.

Marie Louise and her aunt were told that they could take one suitcase full of their belongings and had to leave immediately. Winston Churchill was going to be the new resident in their villa and the Soviets had to get it ready for him. They told Marie Louise that they could return 8 weeks later.

Unfortunately after she left the area, 8 weeks ended up turning into 45 years until she had the opportunity to visit her home again.

–

Potsdam’s district of Babelsberg had comparatively escaped WWII undamaged and was now under the command of thousands of Soviet soldiers, who would eventually be joined by swarms of American and British military guards.

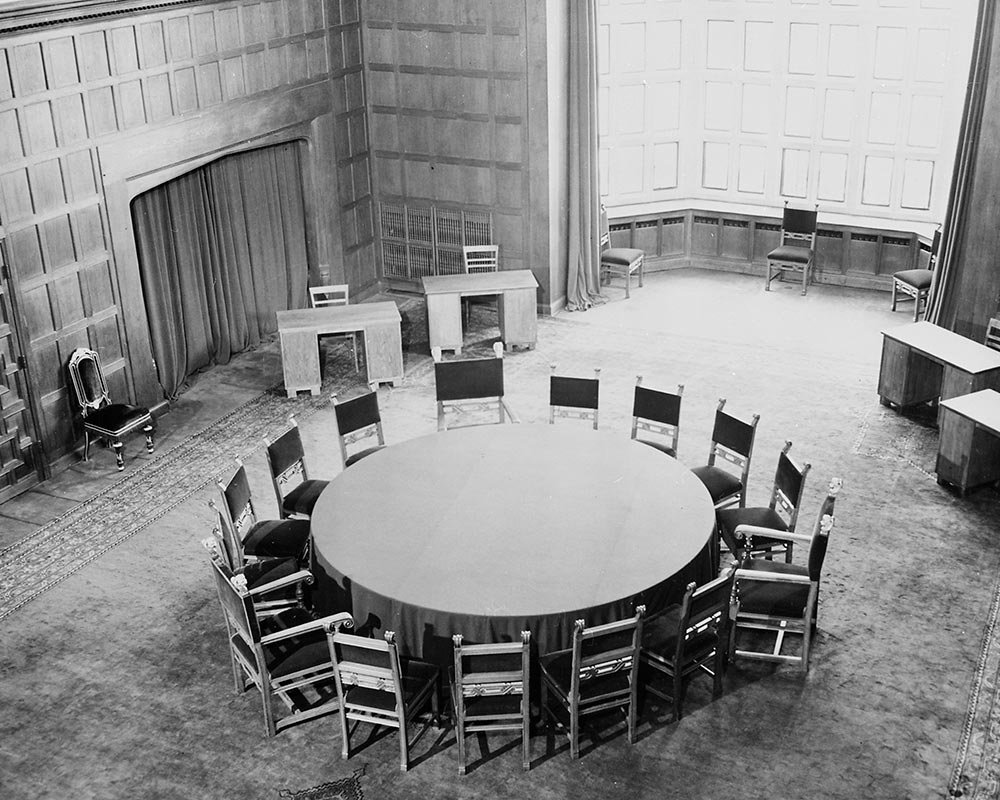

Churchill, Stalin and Truman would be taking up their residences within a short distance from one another in Babelsberg’s lakeshore community. A total of twenty-five houses were prepared with the 3 most spacious and prominent each going to The Big Three themselves.

It was the Soviet’s task to get the area ready for each delegation, but the preparation came at a heavy price for Babelsberg’s residents who were still occupying their homes shortly before the work got underway. In most cases homes were aggressively invaded, their residents hastily evacuated, and anything left behind – including cherished personal possessions – was hauled away to make room for confiscated furniture and decorations from elsewhere.

As for the villas that quartered The Big Three, each one had its own unique history that abruptly and tragically ended for its owners.

At the turn of the 20th century, Paul Herpich, grandson of a popular German fur company tycoon, commissioned renown Swedish architect Alfred Grenander – who famously designed some of Berlin’s most familiar subway and elevated train buildings (Wittenbergplatz, Alexanderplatz, Hermannplatz to name a few) – to build him a picturesque country villa on Griebnitzsee at Kaiserstraße 27.

With its architectural style committed to modernism, but still bearing the traditional features of a villa, it would serve as Stalin’s residence during the Potsdam Conference.

Paul Herpich died in 1923 and some of the only available sources to date indicate that his wife – who was still living in the villa in the spring of 1945 – “had been unceremoniously chased out of her house” when the Soviets arrived. To fit Stalin’s taste in decoration, they immediately cleared out all the furniture except for a large buffet in the dining room that was firmly anchored into the wall paneling. It must have been rather bulky or simply just too heavy to get out the house; at any rate, it – along with two matching smaller dressers on the opposite dining room wall – was the only main piece of furniture to survive the Soviet purge.

And this is mostly what happened to the residences that the Soviets chose. The houses were first looted for real valuables and then everything else was either carted off to the forest or just simply dumped somewhere nearby. The evicted residents most likely never saw any of their furniture, pictures, art, or personal items ever again, and they most likely never had the opportunity to come back until several years later – if at all.

Down the street at Kaiserstraße 2, Villa Müller-Grote’s ending as a private residence arguably ended the most tragically out of all three villas.

Built at the end of the 19th century, the villa became a summer residence for a noted publisher named Gustav Müller-Grote and his large family. This would serve as President Truman’s residence during the Potsdam Conference and was therefore nicknamed “The Little White House”. When Truman moved in, the Soviets had redecorated it with confiscated furniture from elsewhere and his second story suite had a bedroom, bathroom, living room, large office, and a porch that looked out onto lake Griebnitzsee.

Truman found the villa adequate given the circumstances and had been told that the villa had belonged to the head of the Nazi movie industry, who had been sent to Siberia. In fact, what Truman found to be adequate was a far cry from the misery in which Gustav Müller-Grote’s family was living just a short distance away. Truman had not been told who the real owners were or what had happened to them. It was not until years later that Truman learned the tragic truth when he received an extraordinary letter from one of Gustav Müller-Grote’s sons:

“At the end of the war my parents were still living there, as indeed they lived there their whole lives. Some of my sisters moved there with their children, as the suburb seemed to offer more security from bombings…In the beginning of May the Russians arrived. Ten weeks before you entered this house, its tenants were living in constant fright and fear. By day and by night plundering Russian soldiers went in and out, raping my sisters before their own parents and children, beating up my old parents. All the furniture, wardrobes, trunks, etc. were smashed with bayonets and rifle butts, their contents spilled and destroyed in an indescribable manner. The wealth of a cultivated house was destroyed within hours.”

On the lawn that slopes down to the lake where Gustav Müller-Grote’s family used to relax and take refreshing swims during their peaceful summer months now would stand three or four American Military Police Officers in their white gloves and leggings, certainly demonstrating that the victors were in charge now.

–

On visits to Washington to see Roosevelt during the war, Winston Churchill occasionally met with U.S. Senators who were known to carry some weight of influence in Congress. The junior Senator from Missouri, however, had never made it on Churchill’s list.

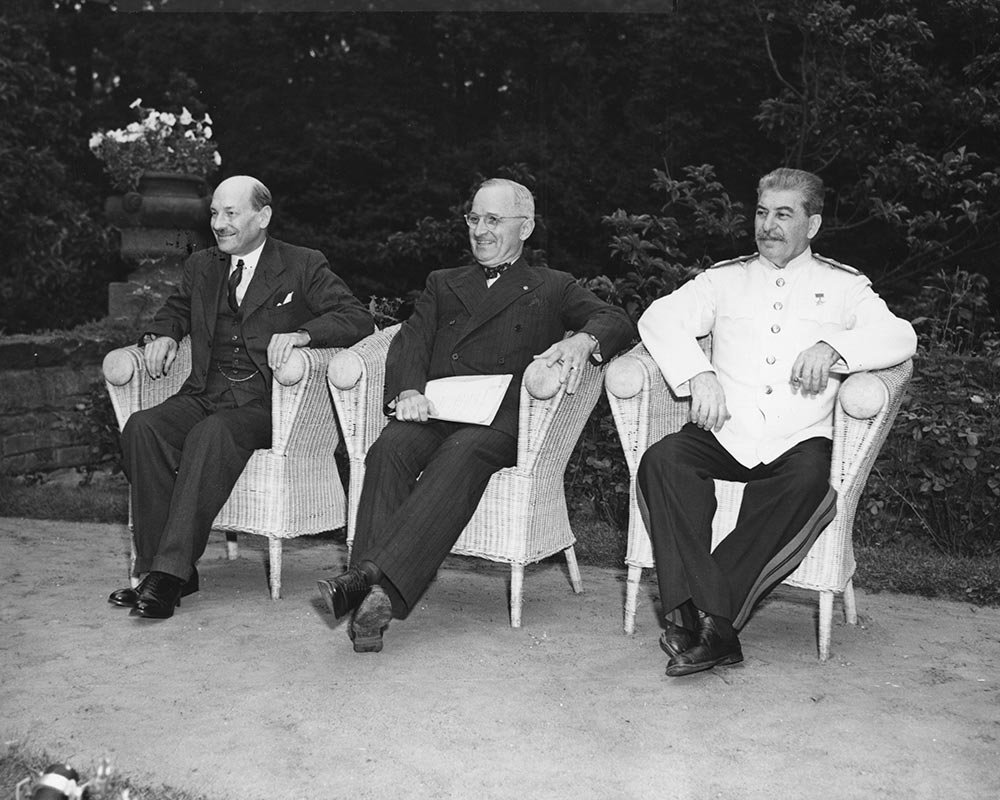

Even though Truman and Churchill had maintained a steady correspondence in the months and weeks leading up to their trip to Potsdam, Monday, July 16, 1945 at 11:00AM at Truman’s new villa marked their very first meeting.

At the beginning of his fourth month in office, Truman boarded the USS Augusta on July 7th and set sail across the Atlantic. He had been to Europe once before as a WWI Captain on the Western Front, but now he was President of the United States, preparing to meet two of the most historic men of the century. Aboard the 10,000-ton ship, Truman continually met with advisors, studied his briefings, constantly read through the minutes from Tehran and Yalta, and looked through memoranda after memoranda, which had been prepared in the State Department, to cover every subject which could conceivably arise at the conference. Truman impressed those around him with his firm and unwavering commitment to preparation. Truman’s Secretary of State, James (Jimmy) F. Byrnes, who had been to Yalta with Roosevelt and was now accompanying Truman to Potsdam, wrote in his memoir:

“At least once a day during the entire trip the President and I would go over them. When the President approved a proposal, it was then prepared for presentation to the conference. Consequently, by the time we landed at Antwerp on July 15, 1945, we had our objectives thoroughly in mind and had the background papers in support of them fully prepared.”

At Antwerp, Truman got off the USS Augusta with an entourage four times greater than the one Roosevelt had with him at Yalta. Along with Byrnes, a few of the other big names with whom he arrived were: his Russian interpreter and diplomat Charles “Chip” Bohlen, Press Secretary and high school friend Charlie Ross, and his Chief of Staff Admiral William Leahy. Leahy, who also attended Yalta, had been a good friend and extremely close personal advisor to Roosevelt during WWII.

With Truman leading the pack, they were all greeted by General Dwight Eisenhower who led the welcoming delegation.

He then boarded his presidential plane, the Douglas VC-54C, The Sacred Cow, (which was escorted by twenty P-47 Thunderbolts beyond Frankfurt) for his three-and-a-half hour flight to Berlin. As his plane headed east and began flying over Germany, he could see blown up bridges and railroads, destroyed factories, and entire cities in ruins down below. Add hundreds of displaced, homeless, and dispossessed people wandering the country to the scene, and Truman’s biographer, David McCullough, sums the calamity up the best:

“Not Abraham Lincoln or Woodrow Wilson or Franklin Roosevelt, not any war President In American history, had ever beheld such a panorama of devastation.”

At 3:40PM on a blazing hot summer day, Truman’s plane touched down at Gatow Airport in the southwest corner of Berlin. It had a modern airfield which was designed by the famous Nazi architect Ernst Sagebiel, who had also designed Berlin’s more famous Tempelhof Airport, in the mid 1930s. Truman’s final destination was a 10 mile car ride south to his new home on Kaiserstraße 2 in Babelsberg.

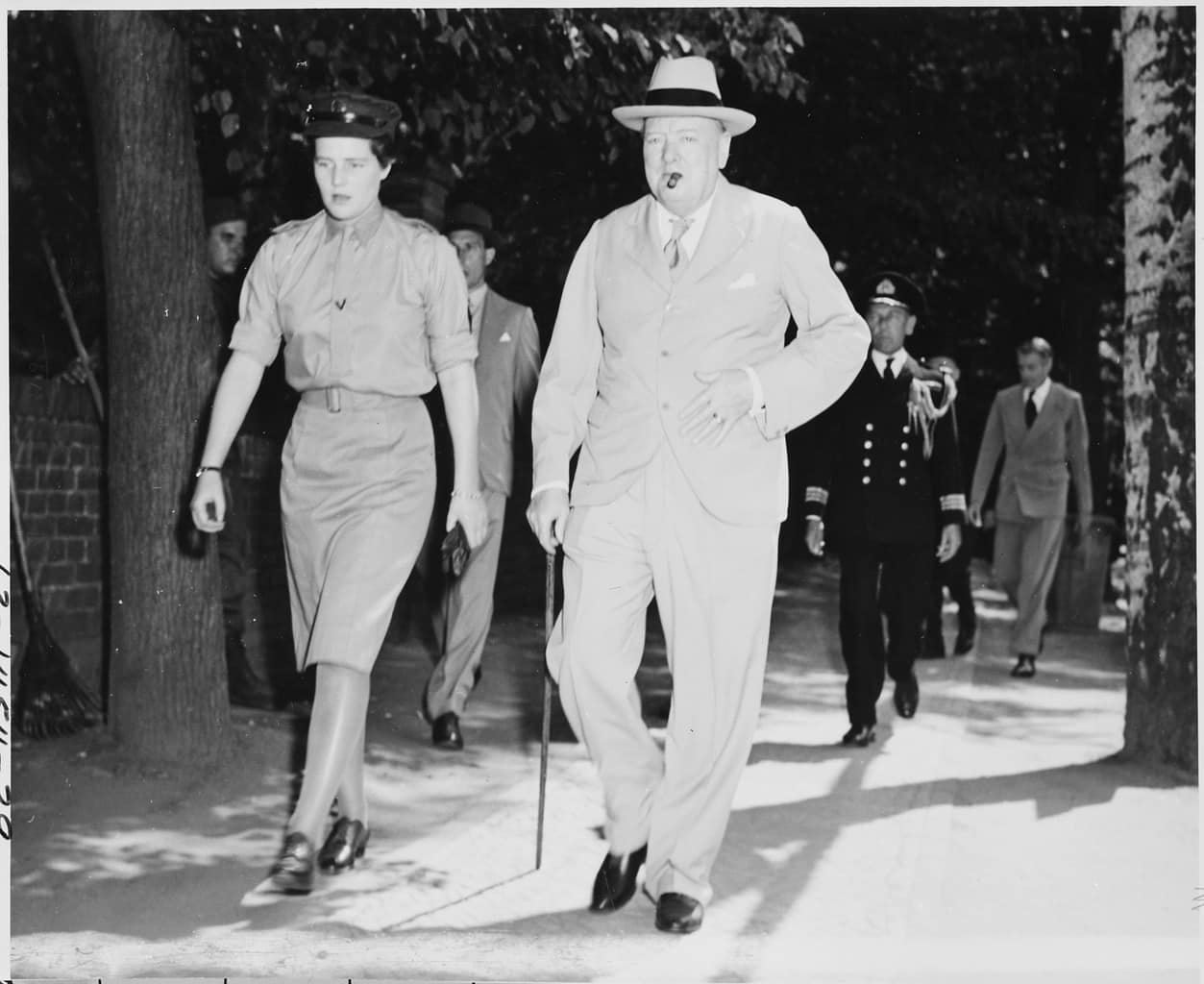

Flying in his Douglas C-54 Skymaster after just enjoying a short family vacation in the south of France, Winston Churchill and his daughter Mary also landed at Gatow just a couple hours after Truman. This would turn out to be the Prime Minister’s unprecedented twenty-fifth and final wartime trip as the leader of the United Kingdom – a conclusion of which he would learn a little over a week later.

Meeting President Truman was of top priority for Churchill and he made it his first order of business on this day. 11AM was the time for which their meeting was scheduled and Churchill arrived at Kaiserstraße 2 right on time. Eager to also meet the President of the United States, Mary was accompanying her father on this late morning call, which was actually quite early for the Prime Minister. During the visit she apparently made the comment to Truman’s military aide and personal friend, Harry Vaughan, that her father had not been up this early in ten years.

Nor had Churchill prepared himself for the Potsdam Conference in anything like the way Truman had. He could not be bothered to look at briefings and he showed up in Potsdam with no agenda. He really did not think he needed to. His plan was to act on intuition and accumulated knowledge, as Roosevelt had at Yalta, and he used his time on his recent vacation to meditate and mentally prepare. Playing a pivotal role in setting up a free and democratically prosperous Poland was at the very top of Churchill’s agenda. Poland had been the cause for which the United Kingdom had entered WWII and seeing it fairly treated and knowing it would have a new flourishing future of self governance was of the utmost importance to Churchill at the end of the day.

He was also 70 years old and decidedly looked his age.

He sounded tired and seemed rather discouraged. Great Britain had just held national elections on July 5th and the results would not be in for a week or so until all the ballots overseas had come in. Given the fact that the current British government would be playing a key role in orchestrating a peace treaty for a defeated Germany – not to mention the fact that WWII was still raging on in the Pacific – holding these elections, which actually could have been deferred until after the war, was an obtuse decision. But Churchill still decided to go ahead with it on the advice that his popularity was at its peak. While there were many who felt that his party would triumph to victory, Churchill himself was privately not so sure. He even personally invited his challenger and opposition party leader, Clement Attlee, to join him at Potsdam should there be a change at the helm.

So at 11AM that familiar stout figure and his even more familiar jutting cigar met the new President of the United States. The two world leaders visited for about two hours and according to Truman, no business about the Conference was considered. Contrary to popular myth, Truman made a very strong impression on Churchill. “He says he is sure he can work with him,” Mary Churchill wrote to her mother in a letter. And asked later by his friend and physician whether or not Truman had any determination, Churchill replied, “He is man of immense determination.”

But the new president from the Midwest had not been impressed by the Prime Minister’s flattery. “He gave me a bunch of hooey about how great my country is and how he loved Roosevelt,” he wrote later that day in a letter to his wife Bess. “Well, I’m sure we can get along if he doesn’t try to give me too much soft soap!”

Meanwhile, Stalin was nowhere to be seen. He was staying up the road from Truman on Kaiserstraße, but all anyone could see were a handful of guards keeping watch on the property. Where Stalin was and why he had not arrived in Potsdam yet were not known. At any rate, this meant that the Conference would have to be postponed for a day and it also meant that Churchill and Truman now had some unexpected free time as they waited for Stalin to arrive.

–

Following Churchill’s visit and learning that the Conference would be delayed a day, Truman wanted to drive up to Berlin to take a tour of what was left of the former Nazi capital.

For months, the city had been the target of Allied bombs with over 68,000 tons being dropped in over 350 air raids from 1940-1945. It was also the site where WWII came to an end after the Soviets engaged in a ferocious man-to-man 12 day combat with what was left of Hitler’s armies during the Battle of Berlin. Although Truman had witnessed the horrors of war as a soldier on the Western Front during WWI, nothing he had seen then could have prepared him for what he was about to witness. He would write in his diary later that evening:

“Then we went on to Berlin and saw absolute ruin. Hitler’s folly. He overreached himself by trying to take in too much territory. He had no morals and his people backed him up. Never did I see a more sorrowful sight…We saw old men, old women, young women, children from tots to teens carrying packs, pushing carts, pulling carts, evidently ejected by the conquerors and carrying what they could of their belongings to nowhere in particular…I thought of Carthage…Rome…Babylon…Alexander…Darius the Great – but Hitler only destroyed Stalingrad – and Berlin.”

Churchill also decided that he wanted to tour a devastated Berlin. Upon entering the city, he and his party drove east through the Tiergarten on the Charlottenburger Chaussee – today’s Street of the 17th of June – that leads to the Brandenburg Gate.

They first went to look at the ruins of the Reichstag and examine the area around the iconic building where WWII in Europe had come to an end just a couple of months before.

There was a crowd of Germans that quickly began to gather around as the whisper of Churchill’s name spread. There were detectives in Churchill’s party and soldiers not far away, but the Prime Minister walked as a free man in the streets of Berlin. That was a new thing for the German crowd to see — a world-famous national leader just out casually sightseeing. “He looks good, the old man,” one German said, and another muttered, as if he could scarcely believe his eyes, “So that is supposed to be a tyrant, is it?”

He finally made his way over to the ruins of Hitler’s New Reich Chancellery building for a thorough tour of the grounds and the government buildings surrounding it. His Foreign Minister, Anthony Eden, commented that he recalled seeing Hindenburg in the (old) Reich Chancellery next door just a short time before Hitler had become Chancellor in 1933. After they dispersed to wander in the direction that their curiosities led them, Churchill eventually made his way into the backyard of the Chancellery and sat down at the entrance of the bunker where the Nazi dictator had taken his life 30 feet beneath the ground on April 30. Churchill himself had been down there to examine it, but he did not stay long.

Now he was back above ground and waiting for the others in his party to return.

Sitting above Hitler’s bunker in the blazing sun, he must have had several thoughts racing through his head as he gazed at the heaps of destruction surrounding him.

The foundations of a lasting peace in Europe must now be laid at Potsdam. A lasting peace that would prevent another tragic conflict of unprecedented proportions from ever happening again. And a lasting peace that would guarantee those nations whose people had suffered under Nazi militarism and fascism the opportunity to freely and independently govern themselves.

Both Churchill and Truman had a lot to think about during their afternoon in Berlin.

**