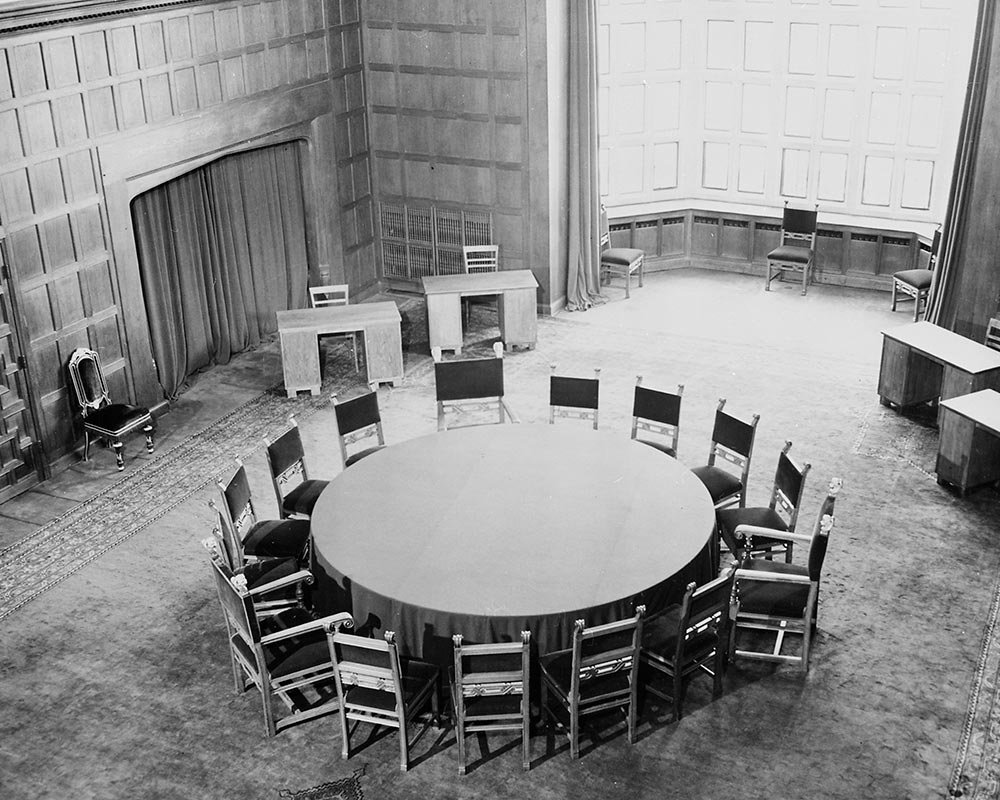

In the days leading up to the British delegation’s departure from Potsdam on July 25th, it is safe to say that the uncertainty regarding the country’s elections had been weighing rather heavily on their minds and adding extra anxiety to the already tense rounds of negotiations. While sitting at the roundtable in Cecilienhof, they all knew that the British people had voted and that they had already selected a leader, but no one knew the outcome yet.

Almost everyone at the conference expected the Conservatives to win, but the margin of victory and the exact composition of the new government remained unknown. The Soviet delegation could not imagine a scenario under which the British people would vote Churchill out of office, and so they continued to overlook and ignore Attlee.

Ironically, Attlee had defied his own party and supported Churchill’s initial desire to postpone the election until after the defeat of Japan. A postponement would have kept the national unity government together through the end of the war and also into the crucial period of setting the foundations of peace. However, several of Churchill’s advisors not only urged him to go forward with the elections – citing that he was at the peak of his power and that the Conservatives would claim a landslide victory – but there were also several senior members in the Labour Party who were urging immediate elections in order to begin the process of implementing the party’s postwar program for the introduction of domestic reforms. Churchill’s decisions to move on with the elections in the end upset several Conservatives who had hoped to keep the stability of the coalition government in place until war had come to an end in the Pacific.

The outcome of the elections spawned a historic shock as it was, instead, Attlee’s Labour Party that claimed a landslide victory. The Conservative majority in the House of Commons disappeared as their number of seats plummeted from 585 to 213. Labour, with 393 seats, now emerged as the dominant party, meaning that Clement Attlee would return to Potsdam as the new Prime Minister of Great Britain.

Attlee was born in 1883 and grew up in an upper middle-class family in London. During his youth he was educated at the historic Haileybury College boarding school before attending the University of Oxford where he began to study law. In 1905 he began regular visits to London’s impoverished East End where he did volunteer work at a settlement house that was financially supported by Haileybury College.

After eventually taking up residence in the house, it was here where he began to lose faith in the existing order as he began to see his political views move steadily to the left and his commitment to ethical socialism begin to grow. During his tenure as prime minister, he would go on to enlarge and improve social services and the public sector in postwar Britain, nationalizing major industries, as well as the public utilities, and creating the National Health Service (NHS), which is still in place today.

The son of a prosperous London lawyer, Attlee was from the city’s charming southwest district of Putney, which was also home to some notable names in British history, like Thomas Cromwell, who served as chief minister to King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

Cromwell was instrumental in arranging the King’s marriages and annulling them. A fierce opponent to Rome and one of the most powerful proponents to the English reformation, he oversaw Henry VIII’s failure to obtain the Pope’s approval for an annulment he was seeking in 1534, which led to Parliament endorsing the King’s claim to be the Supreme Head of the Church of England, which now gave him the authority to annul his own marriages from there on out. Two years later King Henry VIII broke away from Rome, seized all assets from Catholic churches throughout England and Wales and declared himself the established head of the ‘Church of England’.

Henry VIII, from the House of Tudor – whose architectural style flourished throughout England and Wales during the Tudor period and was the inspiration for the architectural style of the Cecilienhof Palace in Potsdam centuries later – had a falling out with Cromwell over an annulment in 1540 and the King had him arraigned, held accountable and executed for treason at Tower Hall in London.

Nearly four centuries later, Attlee was now in the same city making initial arrangements for the formation of a new government – including the appointment of Ernest Beven as the new British Foreign Secretary – as the head of a country that was more concerned about rebuilding Britain after the war and focusing on domestic reform to even care about holding Attlee (and Churchill for that matter) accountable for anything that took place in a Tudor palace back in Germany.

Great Britain had seen its greatness slip away by the summer of 1945 and Attlee was now the person who would take the first major steps of transforming the country into a ‘modern Britain’ and thus giving its people so much more to anticipate or concentrate on than a Soviet-occupied Poland or a Germany that would eventually become divided.

–

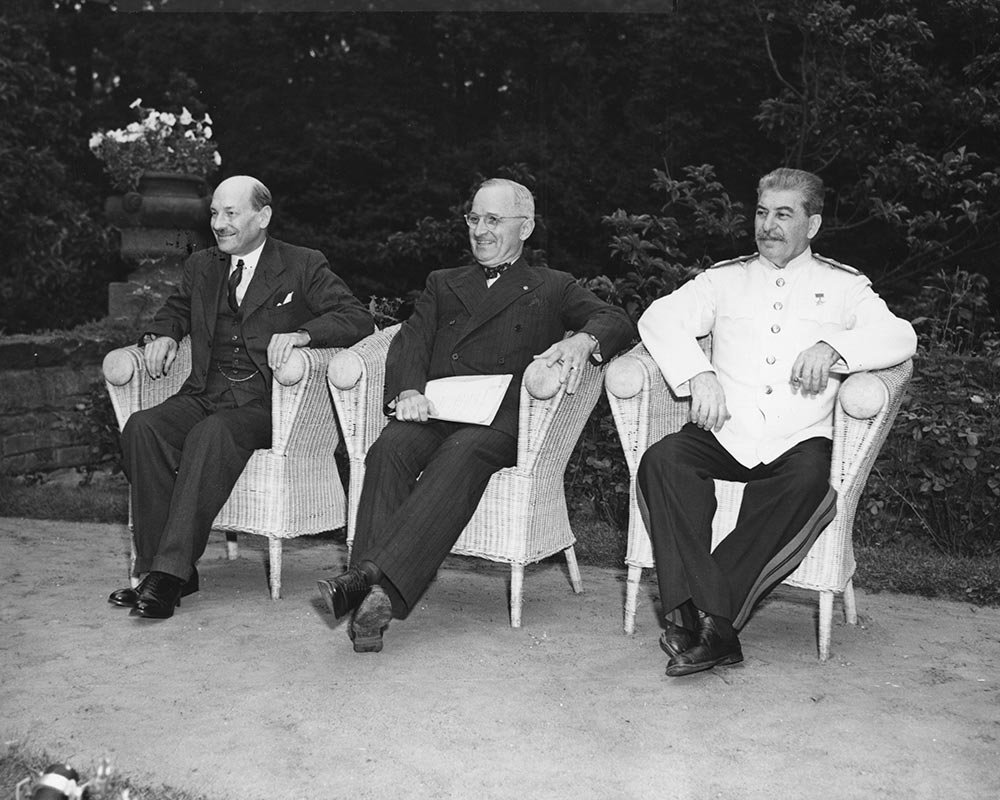

Early this evening, Clement Attlee, Ernest Bevin and the rest of the British delegation arrived from London at Berlin’s Gatow Airport and were driven to their quarters in Babelsberg. Before making their way to Cecilienhof as the new heads of the British delegation, Attlee and Bevin stopped in at the ‘Little White House’ around 9:30pm to greet President Truman and have a few private words before tonight’s tenth plenary session got underway.

Indeed, Truman was familiar with Attlee since he had sat at the roundtable for all the plenary sessions thus far and had been at a few of the evening social gatherings that the Big Three had taken part in. Now, however, he would be dealing with him one-on-one and Truman would quickly see that this modest, soft spoken, seemingly uncharismatic new leader – who had the look of an aging university professor – was much different than the stout figure with the scowl, upraised V-sign and jutting cigar – who had a phenomenal of the English language – that Truman had met twelve days earlier in the same place.

Jimmy Byrnes gave his account of how the first meeting with two new British leaders had gone years later:

“Soon after their arrival, Mr. Attlee and Mr. Bevin called on the President and the four of us discussed the work of the conference. The President mentioned the Soviet demand for East Prussia and indicated on a map the changes in the boundary lines of Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union that thus would be affected. Mr. Bevin immediately and forcefully presented his strong opposition to those boundaries.”

Chief of Staff William Leahy concisely recalled the meeting years later as well by highlighting the two most contentious issues of the conference thus far:

“Prime Minister Attlee and his newly appointed Foreign Minister, Ernest Bevin, arrived shortly after 9pm. and called on the President. Byrnes and I were present and the conversation quickly centered on the possibility of settling the Polish boundary question and reparations.”

And finally President Truman summed up a little bit of both of Byrnes’ and Leahy’s account in a very personal letter he wrote to his wife the following day:

“The British returned last night. They came and called on me at nine-thirty. Attlee is an Oxford man and talks like the much overrated Mr. Eden and Bevin is an English John L. Lewis…(Lewis was a leader of organized labor who served as the president of the United Mine Workers of America, and who – even as a Republican – had supported President Roosevelt in the mid-30s but withdrew his support in 1940 because of FDR’s anti-Nazi foreign policy)….Can you imagine John L. being my Secretary of State? Well we shall see what we shall see. I believe after reading all the minutes, we have obtained all we came for and that there will be a good report to the country. Just the two things to settle but they are the hardest of course.”

Of course, ‘just the two things to settle”’ that Truman was alluding to were – as Leahy pointed out – reparations and Germany’s eastern frontier as it related to the Polish question. These were two issues that had been exhaustively discussed both on and off the record for nearly two weeks, resulting in no progress whatsoever now eleven days into the Potsdam Conference. It was now time for the new British Prime Minister to try his luck at heading his delegation’s negotiations.

–

The ‘new’ Big Three made their way into the conference room at the same time, sat down at the large oak table as usual and President Truman called the tenth plenary session to order at the unusually late hour of 10:30pm. “Shall we take up Poland,” the President asked just after a report on the last two meetings of the foreign secretaries was read.

Stalin gazed across the round table at the two men whom he had just met eleven days ago. They came nowhere close to equaling the status of both their predecessors. They were younger, more inexperienced in foreign affairs than one could have imagined, and they were two men who were nowhere on anybody’s radar when the Grand Alliance had been established two years earlier. Moreover, they were not Roosevelt and Churchill, two men of whom Stalin had a special fondness. This now put the Soviet leader in a unique position. Since the original triumvirate was now gone, Stalin, on many levels, no longer felt himself bound to previous agreements. He would now make a move to push his demands through even more uncompromisingly than he already had been.

But first he need to get something off his chest:

“Last night the Russian delegation was given a copy of the Anglo-American declaration to the Japanese people. We think it our duty to keep each other informed.”

Stalin’s tone seemed to suggest that he was irritated and rather offended by the Americans and British, but then he said nothing further on the subject. The deed was done and all he could do was express his dissatisfaction at a time when he was also in a position to show cooperation to the new world leaders:

“I informed the Allies of the message that I received from the Japanese Emperor through the Japanese ambassador. I sent a copy of my answer to this peace plea which was in the negative. I received another communication informing me more precisely of the desire of the Emperor to send a peace mission headed by Prince Konoye who was stated to have great influence in the Palace. It was indicated that it was the personal desire of the Emperor to avoid further bloodshed. In this document there is nothing new except the emphasis on the Japanese desire to collaborate with the Soviets. Our answer of course will be negative.”

“I appreciate very much what the Marshal has said,” Truman responded. And then he moved to start with that evening’s agenda.

There really was not much each delegation – including the Soviets – could say regarding Stalin’s comments. The United States was more than prepared by this point to force the Japanese to surrender with the atomic bomb and the Soviets needed the war to continue to expand their power and interests in the Far East afterward.

The way in which Italy should pay war reparations dominated tonight’s plenary session. All three leaders were adamant on some form of reparations for the suffering it had caused the Allies during the war. After debating in circles about the form in which reparations payments should come, the Big Three agreed that heavy machinery and war equipment would be extracted as payment for peacetime production. At the moment, however, it was difficult to define what could be taken away without affecting the economic life of Italy moving forward. Once again, the topic would be thrown back to the foreign ministers to discuss the details for a final decision.

With just a few days left in the conference, it is safe to say that the Anglo-American delegations had probably come together as far as they could with the Soviets. Given the nature of the private talks between Truman, Byrnes, Attlee, and Bevin before tonight’s session, it would probably be best to fight out what had been the two most contentious issues thus far – reparations and borders – and head home.

**